Arabic bellydance music is a performance-oriented repertoire designed to accompany bellydance styles such as raqs sharqi, baladi, and saidi. It draws on the Arabic maqam modal system and iqa'at rhythmic cycles, creating music that highlights fluidity, ornamentation, and dynamic contrast to support a dancer's narrative.

Typical instrumentation includes melodic voices like oud, qanun, ney, violin section (kemanat), and sometimes mizmar or arghul for folkloric color, supported by a percussion section centered on tabla/darbuka, riqq, dof/daff, and finger cymbals (sagat/ziyafat). Arrangements often alternate between free-rhythm taqsim (solo improvisations) and driving rhythmic sections in common dance grooves (maqsum, baladi, saidi, malfuf, masmudi).

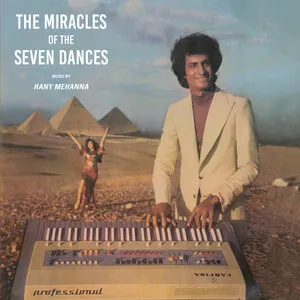

While rooted in Egyptian urban and cinematic traditions, the genre has expanded to include Turkish and Levantine flavors and, in modern productions, synthesizers, drum machines, and string pads. Its hallmark is a dramatic arc—entrance theme, melodic development, drum solo, folkloric vignette, and a rousing finale—crafted to mirror and elevate the dancer’s expression.

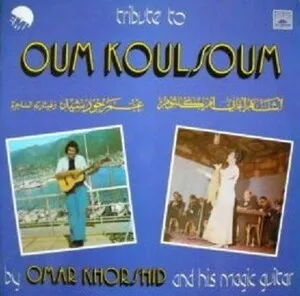

Bellydance as a stage art coalesced in urban Egypt, especially Cairo, from pre-existing social and folk dances. Musically, it drew on Arabic classical traditions (maqam-based suites and taqsim), Ottoman/Turkish art music, and local Egyptian urban/folk styles (baladi, saidi). By the 1920s cabarets and theater revues in Cairo began standardizing a repertory tailored to professional dancers.

Egypt’s booming film industry established the sonic blueprint of raqs sharqi. Large studio orchestras blended oud, qanun, ney, strings, and vibrant percussion, producing grand entrance pieces, lyrical songs, and percussive features for iconic stars on screen. Composers and bandleaders adapted maqam-based melodies to cinematic forms, helping the music reach a mass audience across the Arab world.

Cairo nightclubs and touring revues refined the genre’s set structure: muqaddima (overture/entrance), melodic suite, folkloric segment (e.g., saidi with mizmar), and tabla (drum) solo, ending with a high-energy finale. Studio and cassette culture popularized dedicated “oriental dance” albums, while Turkish and Levantine musicians added regional timbres and rhythms. The core iqa’at (maqsum, baladi, saidi, malfuf, masmudi) became global dance staples.

International dance festivals and instructional media spread bellydance worldwide. Producers blended traditional orchestration with synthesizers, drum machines, and pop hooks, creating show-ready tracks for competitions and stage shows. Percussion-led recordings (for practice and performance) proliferated, and artists outside the Arab world—especially in Turkey, Europe, and the Americas—contributed new arrangements while retaining maqam and iqa’ foundations.

Today, Arabic bellydance music spans classic orchestral arrangements, folkloric vignettes, club-leaning productions, and hybrid sets that segue between taqsim, rhythmic melodies, and virtuosic drum solos. Its core identity remains music crafted to serve the narrative arc and technique of the dancer, honoring maqam nuance, iqa’ groove, and dramatic pacing.

Build sections on common dance cycles:

•Maqsum (4/4): the default, versatile groove.

•Baladi (4/4): earthy, grounded; great for "baladi progression" from free to groove.

•Saidi (4/4): cane-dance energy; often with mizmar/arghul color.

•Malfuf (2/4): brisk entrances or transitions.

•Masmudi Kabir (8/4): weighty, dramatic passages.

•Accentuate DUM (low) and TEK (high) strokes clearly for movement cues; leave space for accents, drops, and stops.