Your digging level

Description

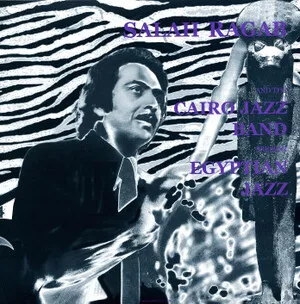

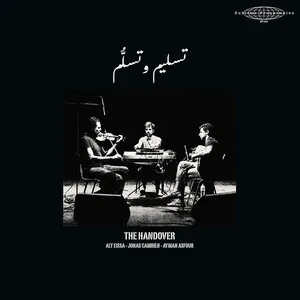

Egyptian music is a broad umbrella that encompasses classical tarab traditions, folk and regional styles, religious chant, and modern popular forms that emerged from Cairo’s recording and film industries.

Its melodic language is built on the maqam system, using scalar “ajnas” and microtonal intervals to create characteristic colors such as Rast, Bayati, Hijaz, Saba, Kurd, and Ajam. Rhythm is organized in cyclical iqaʿat (patterns) like Maqsum, Baladi, Saʿidi, Malfuf, Wahda, Samaʿi Thaqil (10/8) and others.

Core timbres come from the takht and firqa ensembles—oud, qanun, nay, riqq, tabla (darabukka), violin/kaman, with mizmar, rababa, kawala, and arghul in folk settings—while later pop integrates accordion, keyboards, guitars, drum kits, synths, and samplers. Performance features vocal melisma, heterophony, and improvisations such as taqsim, layali, and mawwal.

From the early 20th-century nahda (renaissance) through the mid‑century “golden age” of long songs and film musicals, to shaabi street music and today’s mahraganat and hip‑hop, Egyptian music has continually shaped and reflected culture across the Arabic‑speaking world.

History

Egypt’s musical roots reach back to Ancient Egypt, with temple, court, and folk practices leaving conceptual traces (processional rhythm, antiphony, framing instruments) that later interfaced with Coptic chant and the broader Arabic maqam tradition.

In Cairo and Alexandria, the nahda (renaissance) coalesced around the takht ensemble (oud, qanun, nay, kamanja/violin, riqq). Commercial recording and cafés of the 1900s–1920s helped standardize repertories, forms (dawr, taqtuqa, qasida, samaʿi), and iqaʿ cycles. Ottoman-era aesthetics and Turkish classical practice intermingled with local styles.

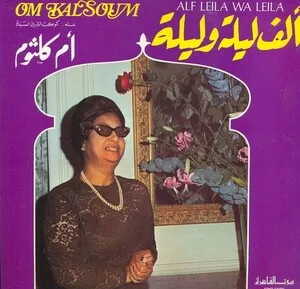

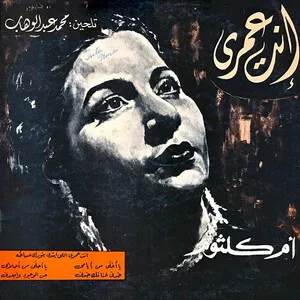

Cairo’s film studios and radio created a pan‑Arab audience. Composers like Mohamed Abdel Wahab and Riad Al Sunbati expanded orchestration (firqa with strings, accordion) and harmonic devices while retaining maqam logic. Iconic voices—Umm Kulthum, Abdel Halim Hafez—popularized the long song, sophisticated modulations, and ecstatic tarab performance culture.

Parallel to urban classics, folk lineages thrived: Saʿidi (Upper Egypt) with mizmar and tahtib dance rhythms; delta and fellahi songs; Nubian traditions (distinct scales, percussion) later refracted into urban pop; and religious spheres including Coptic hymnody and inshad (Sufi praise).

From the 1970s, cassette culture boosted shaabi (urban street music) and dance‑oriented styles. The 1980s–1990s saw al‑jeel and synth‑pop aesthetics (e.g., Amr Diab) shaping Arabic pop. In the 2010s, mahraganat (aka electro‑chaabi) fused auto‑tuned vocals, hard electronic beats, and shaabi attitudes, while Egyptian hip hop and trap‑shaabi hybridized local rhythms and slang with global rap production.

Through cinema, radio, and touring stars, Egyptian music set benchmarks for performance, repertoire, and production across the Arabic world—its maqam‑based melodies, iqaʿ grooves, and tarab ethos continuing to inform bellydance music, Arabic pop, and contemporary urban genres.