Wolof music refers to the traditional and contemporary musical practices of the Wolof people of Senegal (and in parts of The Gambia and Mauritania). It centers on richly layered percussion, call-and-response vocals, praise-singing by hereditary griots (gewel), and dance-driven forms.

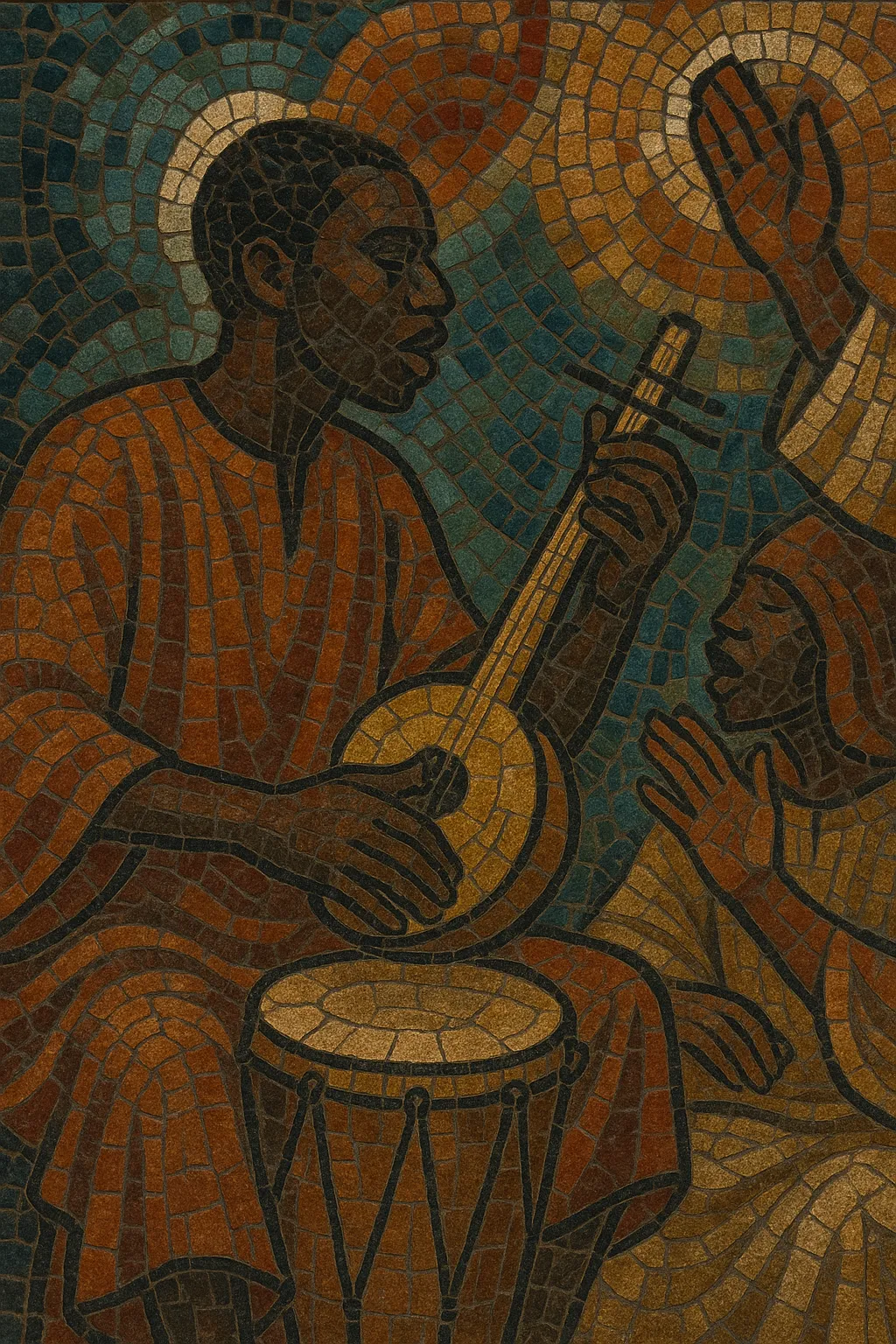

Core timbres come from the sabar drum family (played with one stick and one hand), the tama (talking drum), and the xalam (a skin-stringed lute). Vocals often alternate between solo griot lines, antiphonal choruses, and spoken-sung poetic declamation (taasu), all delivered in Wolof language. Melodically, pieces gravitate around modal centers rather than extended harmonic progressions, while rhythmically they employ polyrhythms, off-beat accents, and dramatic breaks to cue dance and movement.

In the late 20th century, these Wolof foundations powered the rise of mbalax, which fused sabar patterns with Afro-Cuban, pop, and jazz elements. Today, Wolof aesthetics remain audible across Senegalese popular styles and in global worldbeat collaborations.

Wolof musical practice coalesced alongside the political and cultural life of the Wolof states (including the Jolof Empire from the 14th–16th centuries). Music was embedded in rites of passage, courtly ceremonies, praise-singing, and community dance. Hereditary griot families (gewel) curated genealogies, extolled patrons, mediated social memory, and trained successive generations in repertoire, drumming vocabulary, and poetry.

The sabar ensemble (various drums played with stick-and-hand technique) provided dance music with propulsive, syncopated rhythms and showpiece breaks. The tama (talking drum) added speech-like inflections, while the xalam lute carried modal themes and accompaniment. Vocal performance combined sung refrains, melismatic lines, and taasu—rhythmic, incantatory spoken-sung poetry.

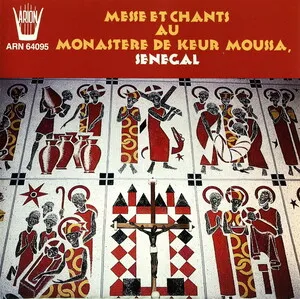

From the 15th century onward, Islam profoundly shaped Wolof cultural life. Sufi orders (notably Mouride and Tijaniyya) encouraged devotional singing, zikr-like chant, and poetic recitation, which influenced vocal delivery, text themes, and modal sensibilities. Trade routes connected Wolof musicians to Maghrebi and broader Arabic musical ideas.

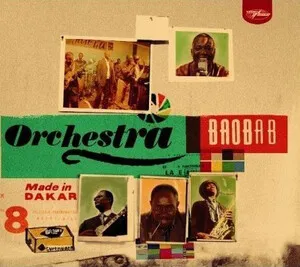

In the 20th century, radio, recordings, and urban dance bands brought Afro-Cuban and jazz harmonies to Senegalese cities. Wolof musicians absorbed clave-informed phrasing while maintaining sabar-rooted rhythmic language, setting the stage for hybrid popular forms.

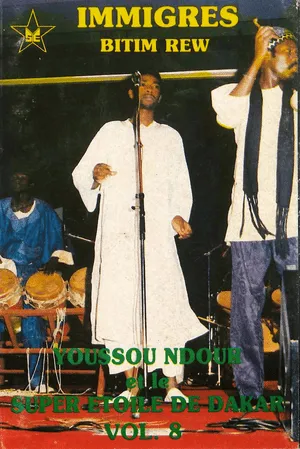

Bands such as Étoile de Dakar (with Youssou N'Dour) crystallized mbalax by placing sabar breaks and tama riffs at the center of electric band arrangements. This sound foregrounded Wolof rhythmic aesthetics while embracing guitars, keyboards, and global pop song structures. Mbalax became Senegal’s signature popular style and a pan-African reference point.

From the 1990s onward, Wolof artists collaborated internationally, feeding into worldbeat, afropop, and fusion projects. While studio production modernized (drum kits, synths, and sampling), core Wolof elements—sabar groove architecture, griot poetics, and the vitality of dance—continue to define the music at ceremonies, stages, and festivals worldwide.