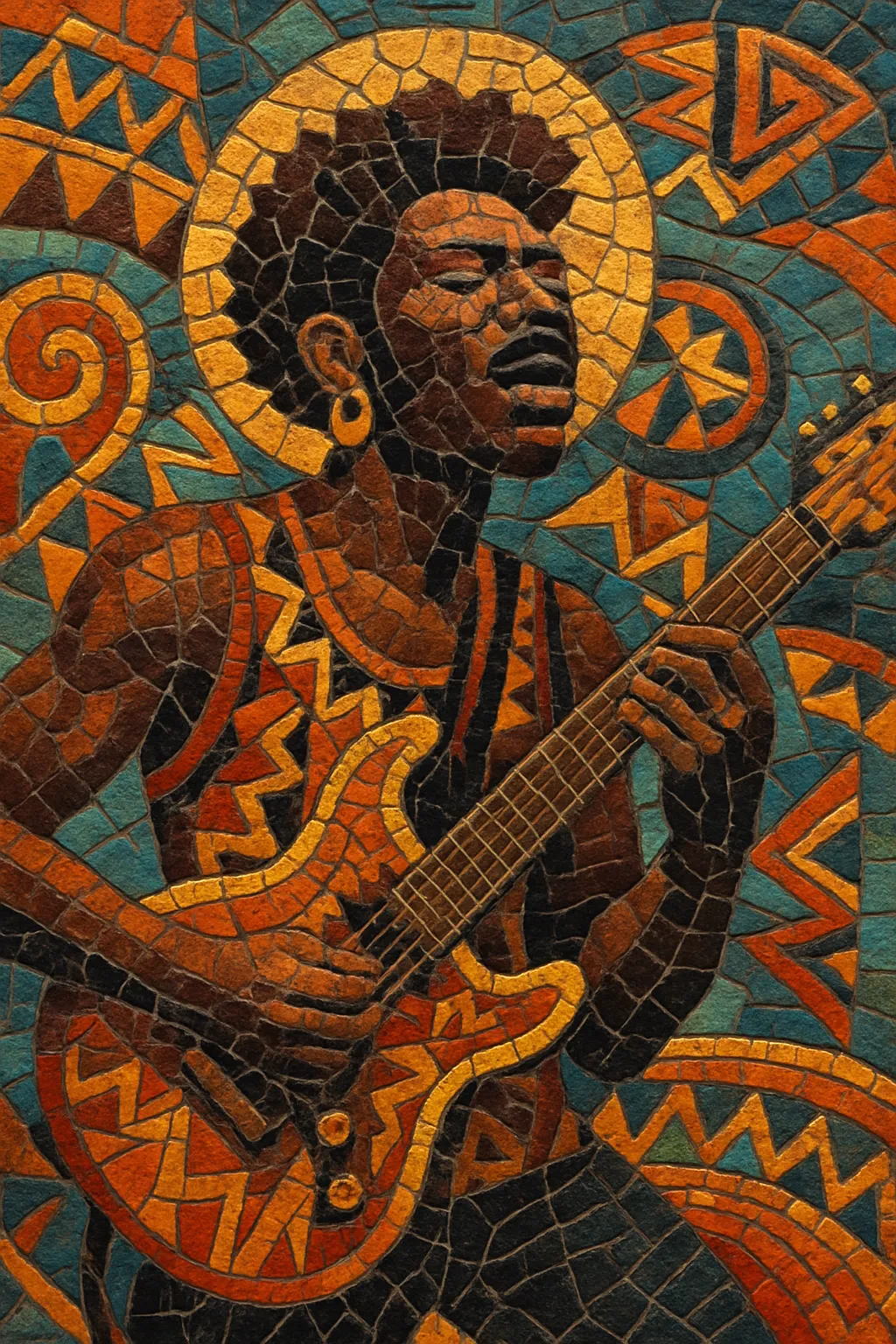

Afro-funk is a groove-driven fusion that marries the syncopated punch of American funk with West African rhythmic traditions such as highlife and jùjú.

It features tightly interlocking rhythm sections, ostinato bass lines, bright horn riffs, call-and-response vocals, and guitar textures that often use wah-wah, palm-muted chanks, and cyclical vamps.

While rooted in dance-floor energy, afro-funk retains a strong sense of locality—languages, proverbs, and social themes are woven into songs—making it both a party music and a vehicle for cultural expression.

The sound flourished in the 1970s across West Africa, especially Nigeria, Ghana, and Benin, with some bands based in diasporic hubs like London, creating a pan-African, cosmopolitan take on funk.

Afro-funk emerged as West African bands absorbed American funk and soul coming via radio, records, and touring artists. Musicians blended these grooves with local frameworks—especially Ghanaian highlife and Nigerian jùjú—retaining polyrhythms, call-and-response, and cyclical song forms while adopting new electric instrumentation and horn arranging styles.

The 1970s was afro-funk’s defining decade. In Nigeria, Ghana, and Benin, groups forged a hard-grooving, horn-forward sound suited to both nightclubs and community gatherings. Studios captured live-in-the-room power: drum kits interlocked with congas, shekere, and claps; bass guitars laid hypnotic ostinatos; guitars used wah-wah and muted patterns; and horn sections provided punchy riffs and fanfares. Lyrics ranged from party anthems to social commentary, mirroring the political and cultural currents of post-independence West Africa.

Bands traveled and recorded across borders, and some—like Ghanaian-led Osibisa—operated from London, spreading afro-funk to European stages. The style intersected with afro-rock and the contemporaneous rise of afrobeat, with musicians moving among scenes and sharing personnel, studios, and audiences.

By the early 1980s, shifts toward disco, boogie, and later pop-oriented styles slowed afro-funk’s original wave, though its rhythmic DNA persisted in burger-highlife and other hybrids. From the 2000s onward, reissue labels and DJs revived interest, inspiring contemporary bands and producers. Today, afro-funk’s grooves and arranging sensibilities echo through modern Afrobeats, world fusion projects, and live-band club music worldwide.

Start with a locked, danceable groove at medium tempo (roughly 90–120 BPM). Use a drum kit playing a steady backbeat while layering hand percussion (congas, shekere, clave-like patterns) to create polyrhythms. The bass guitar should carry a repetitive, syncopated ostinato that outlines the tonic and fifth, with occasional chromatic approach notes.

Use funk guitar techniques: palm-muted sixteenth-note chanks, wah-wah accents, and short cyclical vamps. Keyboards (electric piano, organ, or clavinet) should comp percussively, reinforcing the groove rather than saturating the harmony.

Write concise horn hooks (trumpet, tenor/alto sax, trombone) that answer the vocals or punctuate sectional changes. Arrange call-and-response figures between horns and singers, and use unison or tight parallel intervals for punch. Keep forms vamp-based with clear breakdowns, shout sections, and dynamic builds.

Favor modal or static-harmony vamps (often Mixolydian or minor pentatonic), with occasional dominant extensions (9, 13) for color. Melodies can be short, chant-like refrains for communal sing-alongs, interspersed with improvised solos (sax, guitar, keys).

Combine party themes, everyday life, and social commentary. Use call-and-response refrains, proverbs, and multilingual lyrics (e.g., English, Nigerian Pidgin, Yoruba, Ewe) to root the music in place and engage audiences.

Aim for a live, earthy feel: minimal overdubs, room bleed, and drum/percussion forward in the mix. Let bass be warm and present, with horns bright but not harsh. Modern productions can emulate tape saturation and slight room ambience to capture vintage drive.