Vietnamese folk music (Dân ca Việt Nam) is a diverse body of regional singing and instrumental traditions that grew from village life, ritual, and oral poetry.

It blends pentatonic-centered modal practice (hơi Bắc, Nam, Oán), supple melisma and ornamentation (luyến láy), and flexible rhythm from free-rubato chants to lively dance meters.

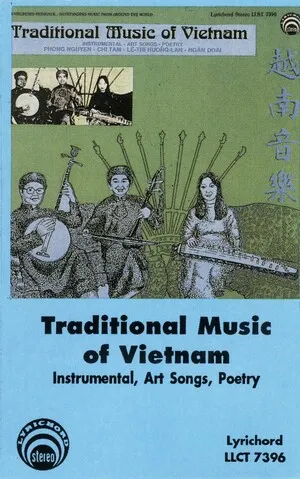

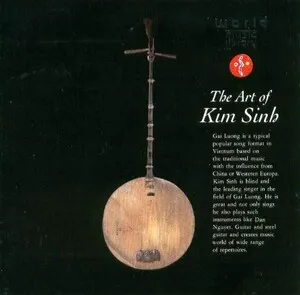

Characteristic textures are heterophonic—voices and instruments carrying the same melody with individual ornamentation—while performance often unfolds as antiphonal dialogue (đối đáp), as in Quan họ love duets. Core instruments include đàn bầu (monochord), đàn tranh (zither), đàn nguyệt (moon lute), đàn nhị (two‑string fiddle), sáo trúc (bamboo flute), trống cơm (rice drum), and wooden clappers (phách).

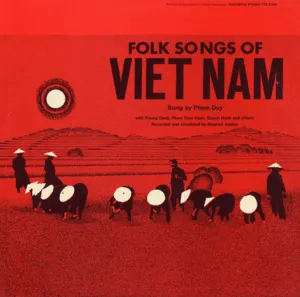

The repertoire ranges from work songs (hò), cradle songs (ru), narrative and ceremonial genres (ca trù), northern theatre song (chèo), to central boat songs (hò mái nhì) and southern long‑meter laments that foreshadow vọng cổ. Themes of love, nature, labor, morality, and community life are set to Vietnamese prosody (lục bát; song thất lục bát; hát nói), making the music inseparable from language, poetry, and local custom.

After Vietnam’s emergence as an independent polity in the 11th century (Lý–Trần dynasties), preexisting village rituals, work chants, and poetic singing crystallized into recognizable folk idioms. Oral poetry forms (lục bát, song thất lục bát) fused with melodic recitation and Buddhist-influenced chant, while Chinese literary culture and theatrical practices shaped narrative singing and proto-theatre.

Distinct regional styles matured alongside linguistic and cultural diversity: Quan họ love duets in Bắc Ninh–Bắc Giang; chèo folk theatre in the Red River Delta; ca trù (hát ả đào) in guild houses; hò and lý song families across the central and southern regions; and court–village exchange around Huế. Heterophony, modal families (hơi Bắc/Nam/Oán), and improvisatory ornamentation became defining features.

Colonial urbanization and print culture documented and circulated folk repertories. Folk idioms fed new theatrical and popular forms: cải lương (southern reformed theatre) drew on hò/lý and narrative singing; urban salon styles adapted ca trù and folk prosody; and recording technology began to preserve master performers and regional variants.

State and community initiatives, conservatories, and scholars such as Trần Văn Khê and Trần Quang Hải catalyzed safeguarding and pedagogy. Several genres (Quan họ, Ca trù, Ví–Giặm) gained UNESCO recognition, spurring revitalization and new ensembles. Contemporary artists sample folk timbres and scales in pop and film, while tradition-bearers sustain living lineages through festivals, temple rites, and apprenticeship.