Your digging level

Description

Udmurt folk music is the traditional music of the Udmurt people, a Permic (Uralic) ethnic group native to the Volga–Ural region. It is primarily vocal, featuring tight unison or gently heterophonic group singing, drones, and parallel motion that creates a plaintive yet luminous sonority.

Melodies tend to be narrow-ranged and modal, often pentatonic or hexatonic, with free or gently pulsed rhythms in laments and more marked duple patterns in dance and ritual songs. Song texts are in the Udmurt language and revolve around agrarian cycles, weddings, family life, nature, and pre-Christian ritual imagery alongside later Christian influences.

Typical instruments include the krez (a local psaltery/zither akin to the gusli), the chipchirgan (Udmurt Jew’s harp), end-blown flutes and reed pipes, frame drums, and, in more recent folk practice, the garmon (button accordion) and violin. Contemporary ensembles sometimes fuse traditional songs with folk-pop or folk-rock arrangements while maintaining Udmurt melodic contours and language.

History

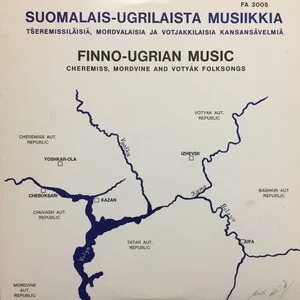

Udmurt folk music grows out of an ancient Permic (Uralic) singing tradition rooted in animist ritual, seasonal work, and life-cycle ceremonies. Before sustained outside contact, songs were transmitted orally within villages, with distinctive local repertoires of laments, wedding songs, children’s songs, and dance tunes. The sound world emphasized unison/heterophony, drones, and modal melodies—hallmarks shared with neighboring Finno‑Ugric communities.

Systematic documentation began in the 1800s as Russian and regional ethnographers collected Udmurt songs and described instruments such as the krez and chipchirgan. Christianization and administrative integration into the Russian Empire brought new song themes and instruments (notably the violin and later the accordion), but core vocal practices remained resilient.

In the Soviet era, Udmurt folk music was promoted within national-cultural policy. Professional and semi-professional ensembles formed, standardizing choreography, vocal blend, and orchestrations for stage presentation. While this professionalization ensured preservation and visibility, it also stylized village practices into arranged choral numbers accompanied by folk orchestras.

After 1991, there was renewed attention to the Udmurt language and grassroots folklore. Archival releases, village expeditions, and youth ensembles helped revitalize lesser-known dialect repertoires. The genre reached global audiences when Buranovskiye Babushki, an Udmurt women’s ensemble, represented Russia at Eurovision 2012, popularizing Udmurt-language folk-pop. Today, practitioners range from village choirs to conservatory-trained ensembles and crossover bands, balancing preservation with sensitive fusion.

%20-%20Finno-Ugrian%20Music%20(Cheremiss%2C%20Mordvine%20and%20Voty%C3%A1k%20Folksongs)%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)