Your digging level

Description

A virtuosic regional shamisen style from the Tsugaru area of Aomori, Japan, tsugaru-jamisen is known for its driving rhythms, percussive bachi (plectrum) strikes, and improvisatory development over folk-song (min'yō) melodic cells.

Players typically use a futozao (thick-neck) shamisen with a large bachi, exploiting the instrument’s sawari (sympathetic buzz) and powerful downstrokes to create both pitch and percussion. Core repertoire pieces such as Tsugaru Jongara-bushi, Tsugaru Yosare-bushi, and Tsugaru Aiya-bushi are treated as frameworks for variation, with free-rhythm introductions blossoming into fast, dance-like sections.

The style balances raw intensity and lyricism, combining rapid tremolo, slides, pull-offs, and offbeat accents with the Japanese jo–ha–kyū sense of pacing. It is performed solo, in duo call-and-response with singers and flutes, or in ensembles, and today appears in concert halls, festivals, competitions, and cross-genre collaborations.

History

Tsugaru-jamisen emerged in the Tsugaru region of Aomori among itinerant blind musicians (often called bosama) who adapted shamisen accompaniment for local min'yō. Figures like Akimoto Nitarō (known as Nitabō) helped shape an energetic, percussive idiom that emphasized rhythmic drive, open-string drones, and spontaneous variation.

In the early 20th century, performers such as Shirakawa Gunpachirō codified techniques and set a core repertoire (notably the many variants of Tsugaru Jongara-bushi). The music’s structure—often a free-rhythm prelude leading into a fast, dance-like section—crystallized, while the futozao shamisen, heavy bachi, and use of sawari formed a recognizable sound ideal.

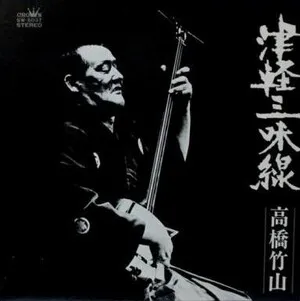

After World War II, Takahashi Chikuzan became a pivotal figure, touring widely and recording solo renditions that brought the style beyond its regional roots. The 1960s–70s Japanese folk and traditional-music revivals further expanded audiences, and regional festivals and competitions (notably in Hirosaki) nurtured new generations of players.

From the 1990s onward, artists such as the Yoshida Brothers, Agatsuma Hiromitsu, and Nitta Masahiro introduced tsugaru-jamisen to global audiences, blending it with rock, jazz, pop, and film/game scoring. Conservatories, competitions, and community ensembles maintain the tradition while encouraging innovation, ensuring the style remains both rooted in min'yō and open to modern collaboration.