Your digging level

Description

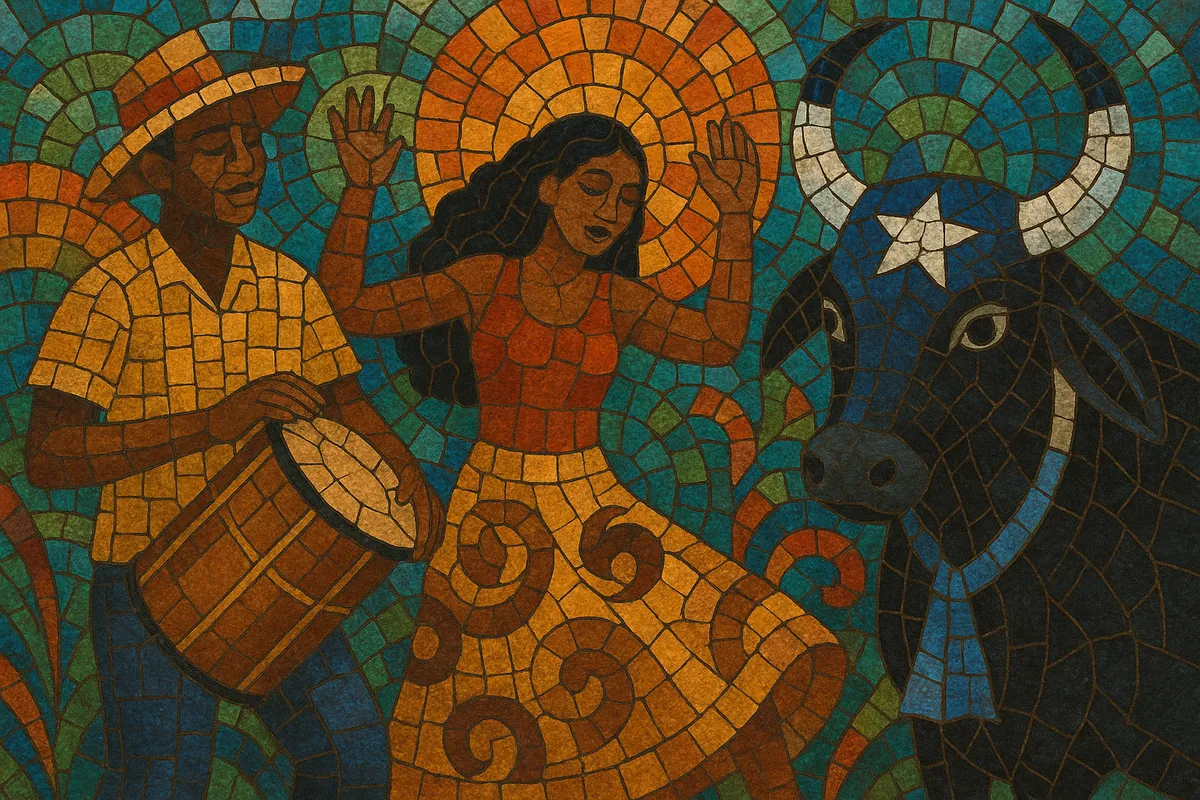

Toada de boi is the song form at the heart of Brazil’s Bumba-meu-boi/Boi-Bumbá tradition, especially prominent in Maranhão and Amazonas. It blends Afro-Indigenous rhythms, narrative vocals, and call-and-response choruses into an anthemic, danceable style performed by large community troupes (bois) during annual festivities.

In Maranhão, the toada is closely tied to processional and courtyard performance with characteristic percussion (pandeirão, matracas), choral refrains, and storytelling about the ox myth. In the Amazon (Parintins, Amazonas), toadas evolved into stadium-scaled pop productions for the Caprichoso and Garantido bois, adding electric instruments, brass, and modern studio polish while retaining the genre’s ritual, communal, and celebratory spirit.

History

Bumba-meu-boi emerged in northeastern Brazil (Maranhão) in the 1800s as a syncretic popular devotion and celebration combining African, Indigenous, and Iberian elements. Its sung repertoire—known as toadas—developed as processional and courtyard songs accompanying the dramatized story of the ox, with call-and-response refrains, steady percussion, and lyrics invoking the characters, saints, and community.

Throughout the 20th century, the tradition spread and diversified. In Maranhão, toadas remained anchored to neighborhood groups and distinctive percussion “sotaques” (matraca, zabumba, orquestra, costa de mão, baixada). In Amazonas—especially Parintins—the form transformed into Boi-Bumbá arena spectacles. There, toadas absorbed influences from carimbó and regional caboclo/Indigenous chants and gradually incorporated electric bass, guitars, keyboards, brass, and large drumlines (Batucada/Marujada).

From the 1970s, musicians like Papete recorded Maranhense toadas, bringing them to national awareness. In the 1990s, televised broadcasts of the Parintins Festival and hits associated with the bois (Caprichoso and Garantido) pushed toada de boi into Brazilian pop consciousness. Voices such as David Assayag and Arlindo Júnior became icons, and groups like Carrapicho carried boi-bumbá–inflected songs abroad.

Today, toada de boi balances tradition and modernity. Parintins productions adopt pop arrangements, sound design, and stagecraft while honoring ritual roles, colors, and symbols. In Maranhão, traditional ensembles continue to foreground percussion, chorus, and neighborhood identity. The cultural importance of the genre was underscored when Bumba-meu-boi do Maranhão was recognized by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage (2019), reaffirming toada de boi’s central role in Brazilian popular culture.