Tango nuevo ("nuevo tango") is a modernist reimagining of Argentine tango that moved the style from the dance floor to the concert stage. It blends the rhythmic drive and melodic idiom of tango with the harmonic language and forms of classical music and the improvisatory spirit of jazz.

Its hallmark sound centers on the bandoneon, supported by chamber-like ensembles—often bandoneon, violin, piano, electric guitar, and double bass—playing tight counterpoint, angular melodies, and sophisticated harmony. Tango nuevo maintains tango’s characteristic pulse and phrasing while expanding it with chromaticism, extended chords, shifting meters, fugal passages, and free rubato.

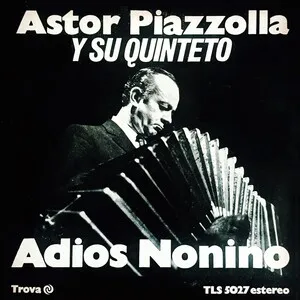

Pioneered by Astor Piazzolla in mid‑20th‑century Buenos Aires, the style is expressive, dramatic, and often introspective, aiming as much at listening audiences as dancers.

Astor Piazzolla, an Argentine bandoneonist and composer trained in both tango and European classical traditions (notably with Nadia Boulanger), formed the Octeto Buenos Aires in 1955. He applied counterpoint, extended harmony, and through‑composed forms to tango material—an approach that broke with the dance‑oriented orchestra típica. Early works faced criticism from tango purists but established the foundation of tango nuevo.

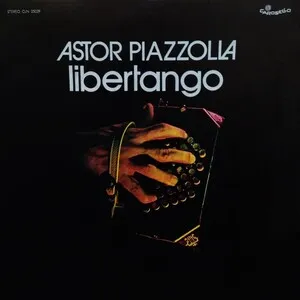

Piazzolla’s ensembles (particularly the Quinteto Nuevo Tango) defined the idiom: bandoneon, violin, piano, electric guitar, and double bass executed virtuosic parts, sharp articulations, and intricate rhythmic interplay. The music drew on jazz phrasing and occasional improvisation, baroque techniques (e.g., fugue), and chamber textures, turning tango into a concert music. Key pieces like Libertango and Adiós Nonino became emblematic.

Tours and collaborations (e.g., with Gerry Mulligan) helped globalize the style. A new generation—Pablo Ziegler, Néstor Marconi, Rodolfo Mederos, and others—extended the language, writing for chamber groups, orchestras, and film while retaining tango’s core rhythmic DNA.

After Piazzolla’s death (1992), tango nuevo’s concert tradition continued through dedicated ensembles and composers. Its harmonic and formal innovations influenced electrotango/electronic hybrids, chamber jazz, and world‑fusion projects. Today, tango nuevo is a living repertoire performed worldwide, with new works and re‑imaginings that balance tango’s soul with modernist craft.