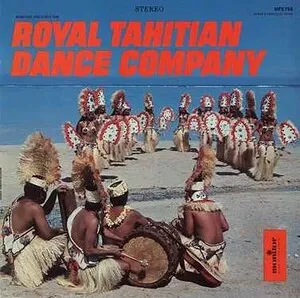

Tahitian music refers to the traditional and contemporary musical practices of Tahiti and the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is centered on powerful communal singing and propulsive drum ensembles that drive social dance and ceremony.

Core forms include the drum-led 'ote'a (fast, virtuosic dance pieces), the song-and-gesture aparima (narrative hand dance), and the polyphonic choral traditions broadly called himene (including the large-choir himene tarava shaped by Protestant hymnody). Signature instruments are the to'ere (slit log drum), pahu and fa'atete (frame and single-headed drums), vivo (nose flute), pū (conch shell), and the rapidly strummed Tahitian ukulele with doubled courses.

Modern Tahitian music also embraces guitars, amplified ensembles, and pop-reggae inflections, yet it retains hallmark traits: layered drum ostinatos, call-and-response vocals, bright modal melodies, and an inseparable bond with dance and storytelling.

Tahitian musical practice predates European contact by many centuries, embedded in Polynesian oral traditions of chant, dance, and drumming used for genealogy, myth, and communal rites. Slit drums (to'ere), frame drums (pahu, fa'atete), nose flutes, and conch shells provided timbral variety and rhythmic power for dance and ceremony.

European contact in the late 18th century and the arrival of missionaries (from 1797) transformed public music-making. While some dance practices were suppressed, new choral styles flourished in church contexts. Indigenous polyphony merged with Protestant hymnody to produce monumental multi-part congregational singing known as himene (notably the himene tarava).

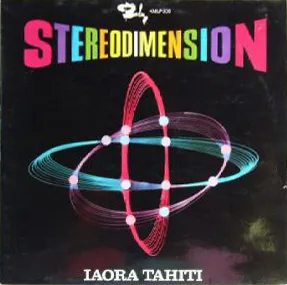

By the late 19th century, secular dance and drumming re-emerged in public festivals (Tiurai), anchoring the modern performance tradition. In the mid-20th century, local bands such as Eddie Lund and His Tahitians popularized Tahitian song forms for radio, records, and the burgeoning hotel/tourism circuit, crystallizing a repertoire that balanced traditional rhythms with accessible harmonies.

From the late 20th century onward, large professional troupes refined high-speed drum choreography and massed choral textures for the annual Heiva competitions (the modern successor to Tiurai). International touring and diasporic schools spread Ori Tahiti (Tahitian dance) and its music across Oceania, Europe, and the Americas. Contemporary acts mix traditional drums and ukulele with pop, reggae, and worldbeat aesthetics while maintaining core markers: interlocking to'ere patterns, call-and-response vocals, and dance-led structures.