Southeastern Brazilian music refers to the rich web of popular and traditional styles that crystallized in the urban centers of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Belo Horizonte, and Espírito Santo. It encompasses historic genres such as choro and samba, mid‑century developments like bossa nova and MPB, and late‑20th‑century urban forms including funk carioca and hip hop.

Rhythmically, it fuses African‑diasporic percussion with European song forms and harmony. Instrumentation ranges from cavaquinho, pandeiro, surdo, cuíca, tamborim, bandolim, and flute in choro/samba ensembles to nylon‑string guitar, jazz‑leaning piano/bass/drums in bossa nova and MPB, and 808‑driven beats and sampling in funk carioca and São Paulo rap.

Harmonically, the region is noted for both the contrapuntal elegance of choro and the sophisticated extended‑chord vocabulary of bossa nova and MPB. Culturally, carnival, samba schools, radio, and the recording industry helped project these sounds nationwide and globally.

Choro coalesced in late‑19th‑century Rio de Janeiro from European dance forms and Brazilian popular practices, setting a template for virtuosic melody, counterpoint, and syncopation. Early urban musics such as lundu, modinha, and maxixe—along with Afro‑Brazilian religious and social percussion practices—fed directly into what would become samba in the 1910s–1920s.

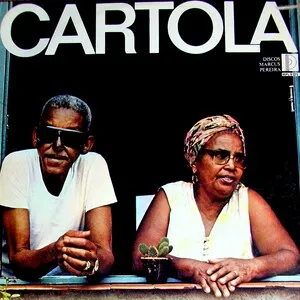

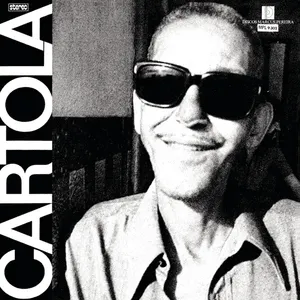

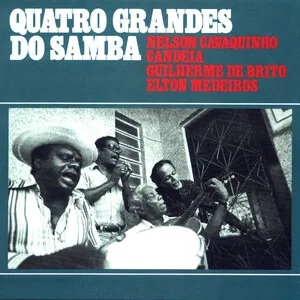

With the rise of radio and the recording industry, Rio turned samba into a national symbol. Carnival marchinhas and samba‑canção flourished, and composers like Pixinguinha bridged choro and early orchestrations. Samba schools institutionalized community performance and pioneered large percussion ensembles.

In late‑1950s Rio, bossa nova married cool jazz harmony to the intimate samba pulse, projecting a cosmopolitan image abroad. In the late 1960s, Tropicália (centered in Bahia and São Paulo) and the wider MPB movement blended samba, bossa, rock, and avant‑garde ideas, often in dialogue with censorship during the military dictatorship. Minas Gerais contributed the Clube da Esquina scene, adding chamber‑like textures and refined songwriting.

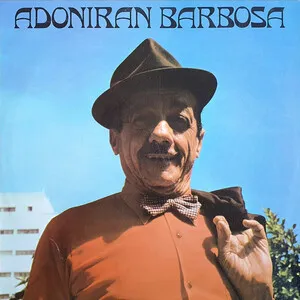

São Paulo became a powerhouse for rock and hip hop, while Rio incubated funk carioca, whose tamborzão beat grew from Miami bass and electro‑funk. Artists like Racionais MC’s narrated metropolitan realities, and timbres from global pop and electronic music entered the regional palette.

Streaming and international collaborations amplified Southeastern styles worldwide. Funk carioca diversified (from conscious to pop‑friendly forms), MPB remained a songwriting bedrock, and samba traditions continued through schools, pagode groups, and roots revivals. The region’s music now fluidly links tradition, jazz‑influenced harmony, and contemporary beat culture.