South American music is an umbrella term for the diverse traditional and popular musics that originated across the continent’s Andean highlands, Atlantic and Pacific coasts, Amazon basin, and Southern Cone.

It blends three deep currents: Indigenous musical practices (panpipes, quena, pentatonic melodies, communal dance-songs), Iberian (Spanish/Portuguese) song forms and harmony (guitars, verse–refrain balladry, dance meters and hemiola), and West/Central African rhythm, call-and-response, and percussion (polyrhythms, syncope, drums and idiophones). The result is a mosaic ranging from Andean ensemble timbres and Afro-Peruvian cajón grooves to Brazilian samba’s percussion batteries and the urban melancholy of Río de la Plata tango.

Across the 20th century, radio, recording, and urbanization transformed regional folk idioms into nationally and internationally recognized styles—tango, samba, choro, cumbia, forró, nueva canción, MPB, and more—while contemporary scenes continue to hybridize with jazz, rock, hip hop, and electronic production.

Before European contact, diverse Indigenous nations developed rich ceremonial and communal musics. In the Andes, panpipe consorts (siku/antara), quena flutes, and communal hocketing textures were common; rhythmic dance music tied to agricultural and ritual cycles shaped social life.

Spanish and Portuguese colonization introduced Iberian dance forms (fandango, seguidilla, jota), plucked chordophones (vihuela/guitar, later charango adaptations), liturgical genres (villancico), and European harmonic practices. Enslaved Africans brought polyrhythm, call‑and‑response, and new percussion, profoundly shaping coastal and plantation regions—especially in Brazil (candomblé, maracatu), the Río de la Plata, and Pacific/Caribbean coasts. Hybrid criollo forms emerged (zamba, cueca, lundu, modinha), often featuring hemiola (3:2) and mixed meters.

Urban centers crystallized national musics: tango in Buenos Aires/Montevideo, choro and early samba in Rio de Janeiro, cueca and tonadas in Chile, and Andean salon/folk repertoires across the highlands. Shellac records, radio, and dance halls standardized rhythms, ensembles (e.g., bandoneón in tango; guitar/cavaquinho in Brazil), and song forms.

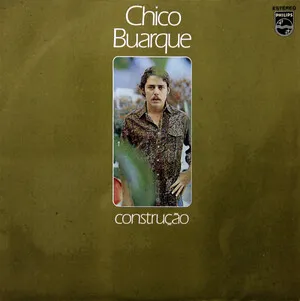

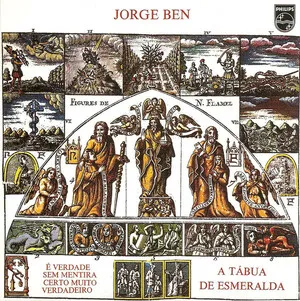

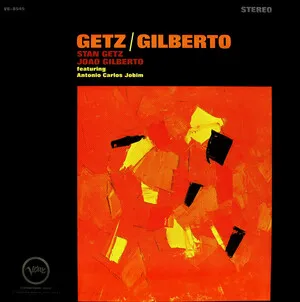

Postwar modernism and mass media carried South American styles worldwide. Bossa nova and MPB reframed samba with jazz harmony; nueva canción tied folk idioms to social poetry; cumbia radiated from Colombia across the continent; forró urbanized Northeastern Brazilian dance traditions. Iconic composers/performers (Jobim, João Gilberto, Violeta Parra, Mercedes Sosa, Astor Piazzolla) globalized the South American sound.

Rock en español and local rock scenes, Afro‑Peruvian and Andean revivals, and electronic fusions (tecnobrega, cumbia villera/nueva cumbia, funk carioca) expanded the palette. Today, artists intertwine traditional rhythms with hip hop, pop, and club production, sustaining a continent‑wide ecosystem that is both rooted and innovative.