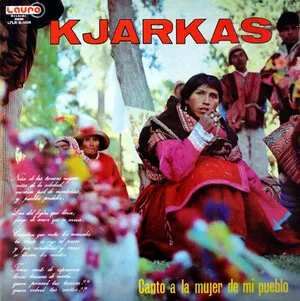

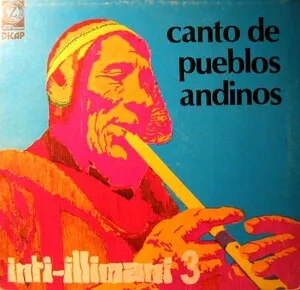

Indigenous Andean music refers to the ceremonial, communal, and dance music of Quechua, Aymara, and other native peoples of the Andean highlands of present-day Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, northern Chile, and northwestern Argentina.

It is characterized by panpipe ensembles (siku/zampoña, antara), end-blown flutes (quena, pinkillu), block flutes (tarka), large double-headed drums (wankara/bombo), and—since the colonial period—the charango. Ensembles often play in interlocking pairs (ira/arca), creating hocketed melodies, dense heterophony, and a powerful collective sound suitable for processions and open-air festivals.

Melodically, pentatonic and hexatonic scales are common, with flexible, non-equal-tempered tunings. Rhythms favor duple meters (2/4) and 6/8 feels, with frequent sesquialtera (3:2) interplay that drives circle and line dances. Vocals tend toward group singing, call-and-response, and timbres that prioritize projection in outdoor contexts. The music is inseparable from agricultural cycles, community identity (ayllu), and ritual calendars.

Archaeological finds (Nazca, Moche, Tiwanaku) show ceramic panpipes, ocarinas, and drums, indicating a millennia-old Andean aerophone tradition. By the 1400s, the Inca state helped standardize ceremonial practices across the highlands, with music central to agricultural rites, warfare, and state festivals. Interlocking panpipe practice (ira/arca pairs), heterophonic group singing, and seasonally specific instrument repertories were already prominent.

After the 16th‑century Spanish invasion, indigenous ensembles persisted while adapting to new instruments (charango, harp, violin) and Christian ritual calendars. Despite suppression of certain rites, music remained a resilient carrier of language, memory, and communal obligations, and it intertwined with Catholic festivals, processions, and local patron-saint celebrations.

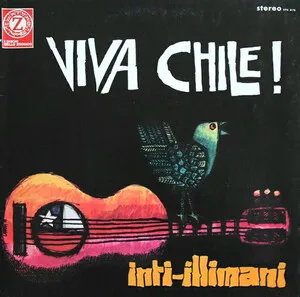

Rural-urban migration brought highland music into cities, radio, and records. Panpipe ensembles (sikuris) from Puno and the Altiplano gained visibility, and master performers codified repertories and instrument-making techniques. Parallel currents—like indigenismo and later nueva canción—spotlighted Andean instruments and aesthetics on national and international stages, often framing them as emblems of identity and resistance.

Today, indigenous Andean music thrives in community festivals (Carnaval de Oruro, Virgen de la Candelaria in Puno), local agricultural cycles, and diasporic contexts. Traditional ensembles maintain non-equal-tempered tunings, seasonal repertories, and collective choreography, while contemporary groups also present concert arrangements and cross-genre collaborations, keeping core practices—siku hocketing, communal drumming, ritual function—intact.