Ryukyuan music is the traditional music of the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa, Amami, Miyako, Yaeyama), characterized by its distinctive pentatonic melodic language, island dialect lyrics, and the signature sound of the snakeskin-covered three‑string lute called the sanshin. It encompasses refined court repertoires (koten ongaku), narrative song, and a rich array of folk and dance genres (collectively shima‑uta), alongside powerful festival drumming traditions like eisa.

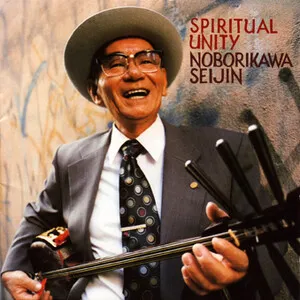

Its timbre is immediately recognizable: nasal yet warm vocals ornamented with slides and a light, flexible vibrato, the dry plucked resonance of the sanshin, and supportive percussion from frame drums and hand instruments such as sanba castanets. Melodically, Ryukyuan songs favor pentatonic modes that omit certain scale degrees (often the 2nd and 6th), creating a bittersweet, floating quality. Songs range from intimate, contemplative ballads to exuberant dance pieces like kachāshī.

Ryukyuan music developed at the crossroads of East and Southeast Asia through the maritime Ryukyu Kingdom. Court forms absorbed diplomatic and ritual influences from Chinese and Japanese traditions, while village songs preserved local dialects, call‑and‑response structures, and communal dance, yielding a living tradition that continues to inspire contemporary pop and world‑music fusions.

The Ryukyu Kingdom emerged as a maritime hub linking Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. Music at court crystallized in this era, adopting ritual and ceremonial frameworks influenced by Chinese court practice and Japanese aristocratic music. The sanshin—derived from the Chinese sanxian—became the core instrument, and the earliest song repertoires were codified with kunkunshi notation.

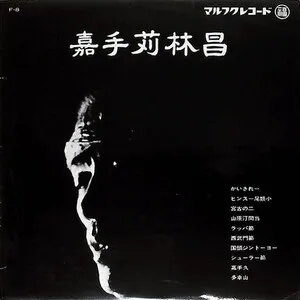

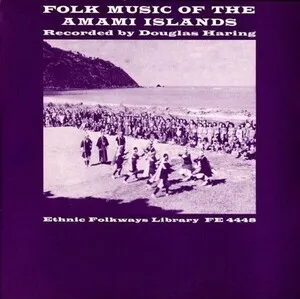

A dual ecology formed: koten ongaku (court/classical) cultivated refined ensembles, formal song cycles, and ritual pieces performed for diplomacy and state ceremonies, while village traditions (shima‑uta) thrived as communal music for work, festivities, and storytelling. Folk music emphasized call‑and‑response, dance (notably kachāshī), and festival drumming such as eisa. Distinct island groups (Amami, Miyako, Yaeyama) developed their own vocal dialects, melodic contours, and rhythmic feels under the broader Ryukyuan umbrella.

After the Satsuma Domain’s 1609 invasion, Ryukyuan culture persisted under political pressure. The sanshin traveled to mainland Japan and catalyzed the emergence of the shamisen, shaping Edo‑period shamisen repertoires. Meanwhile, local court and folk practices continued to evolve, absorbing elements of Buddhist chant and Japanese ceremonial styles, while retaining Ryukyu’s pentatonic aesthetics.

The devastation of World War II and the U.S. occupation challenged musical continuity, yet post‑war radio, recordings, and local preservation movements catalyzed revival. Master performers documented and taught repertoire; women’s vocal ensembles and mixed traditional‑modern bands popularized island songs beyond Okinawa. From the 1970s onward, artists blended sanshin with rock, reggae, and jazz.

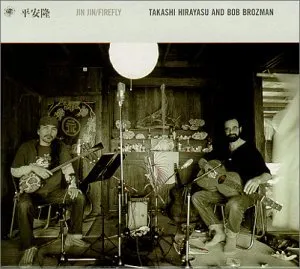

The 1990s brought a wider "shima‑uta" boom across Japan, with hits penned by Okinawan artists entering national charts. Contemporary performers continue to fuse Ryukyuan melody, language, and sanshin with pop, ambient, and world styles. Parallel to these innovations, classical schools and folk associations maintain rigorous transmission of koten and regional styles, ensuring both continuity and creative growth.