Amami shimauta is the traditional island-song style of the Amami Islands in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. It is marked by a striking, ornamented head-voice (falsetto) timbre, flexible rhythm, and poetic texts that evoke seafaring life, love, nature, and work on the subtropical islands.

While related to the broader Japanese min'yō (folk song) and Ryukyuan island-song traditions, Amami shimauta has its own vocal color, melodic turns, and local repertory. Songs are often performed solo with a three‑string lute (a local sanshin/jamisen variant) or a cappella, and may include spirited kakegoe (shouted interjections) from listeners.

In contemporary times, several artists have brought Amami shimauta to wider audiences by fusing its vocal technique and modal flavor with pop, folk, and ambient textures, while community gatherings and competitions continue to sustain the tradition at home.

Amami shimauta emerged in the Amami archipelago under the influence of mainland Japanese min'yō and Ryukyuan island-song practices. By the 1700s, after the Satsuma Domain asserted control (beginning in 1609), distinctive local song repertoires tied to labor (sugar cultivation and fishing), rituals, and social gatherings took shape.

Across the 18th–19th centuries, Amami communities refined a vocal style known for its penetrating, high head voice, intricate melisma, and narrow, carefully placed vibrato. Songs were performed a cappella or with a three‑string lute (a local sanshin/jamisen variant), and settings ranged from domestic celebrations to seasonal events. Flexible rhythmic pacing (free-rhythm introductions followed by steadier sections) and audience interjections (kakegoe) remained hallmarks.

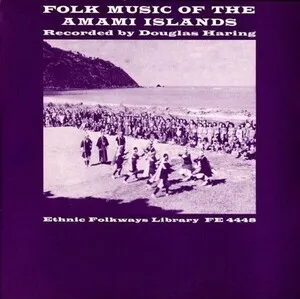

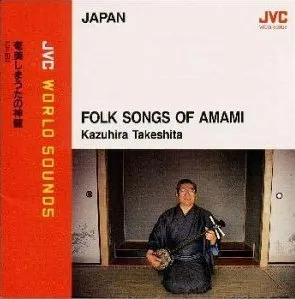

In the 20th century, collectors, local cultural associations, and radio helped document and circulate shimauta. Postwar urban migration brought the style into mainland Japanese folk circuits, while local festivals and competitions preserved transmission on the islands. Recordings from the late 20th century captured both elder tradition bearers and new interpreters.

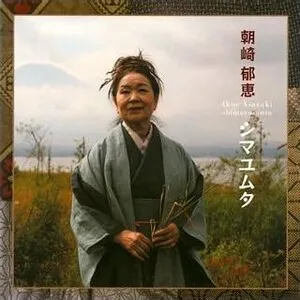

From the late 1990s onward, several Amami-born singers introduced shimauta techniques into J-pop, acoustic folk, and ambient contexts, earning national and international audiences. Today, community stages, schools, and cultural groups maintain the tradition, while artists continue to blend shimauta with modern production in ways that keep its core timbre and modal flavor intact.