Your digging level

Description

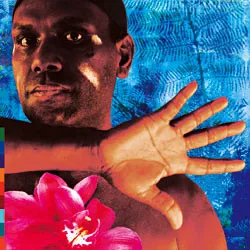

Papuan folk music refers to the traditional and community-based music of the Indigenous peoples of the island of New Guinea, spanning today’s Papua New Guinea and the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Papua. It encompasses hundreds of distinct musical micro-traditions tied to language groups, clans, and ecological zones from coastal islands to highland valleys.

Core soundworlds include the deep pulse of kundu/tifa hand drums and garamut slit drums, bright bamboo flutes and panpipes, resonant conch shells, rattles and seed shakers, and the susap (mouth harp), often used in courtship. Vocals are central: unison or tightly interlocking group singing, call-and-response, vocables, and heterophony are common, with scales ranging from pentatonic and anhemitonic to locally specific tunings and microtonal inflections.

Music functions in ceremony and daily life—initiation and bridewealth exchanges, origin-myth performances, mourning, canoe launches, sago harvests, and warrior dances. Dance is inseparable from the sound, with body adornment, mask traditions, and synchronized movement shaping the rhythm and phrasing. In coastal areas, gong-chime sets and later guitar/ukulele string-band textures intersect with older idioms, while highland aerophone traditions favor bamboo and bone flutes, bullroarers, and powerful communal chant.

History

Papuan musical practices predate written history. Music was (and remains) embedded in social life: it accompanies rites of passage, clan diplomacy and exchange (e.g., bridewealth), hunting and gardening cycles, warfare and peacemaking, and storytelling tied to land and ancestry. Instruments such as kundu/tifa and garamut communicated over distance, while flutes, panpipes, conch shells, and susap mouth harps marked courtship, ritual atmospheres, and dance.

European exploration and colonial administrations brought early ethnographic accounts and cylinder/disc recordings. Missionization introduced Christian hymnody and choral part-singing, which coexisted with (and sometimes reframed) local repertoires. In coastal zones with Austronesian exchange networks, gong-chime idioms and later Western string instruments entered communal musicking.

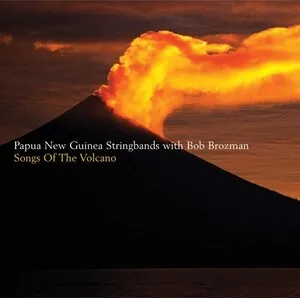

During late colonial and early postcolonial periods, cultural festivals and state cultural bodies highlighted regional styles at “sing-sing” gatherings. Portable guitars and ukuleles catalyzed string-band styles that localized harmony and form while retaining Papuan rhythmic feel, call-and-response, and dance function. Academic ethnomusicology expanded fieldwork, notation, and archiving.

Artists and cultural leaders foregrounded indigenous sound as political expression. In West Papua, Arnold Ap and the group Mambesak curated and modernized traditional songs to assert Papuan identity; in Papua New Guinea, ensembles fused ritual materials with contemporary instruments, raising global awareness of local forms.

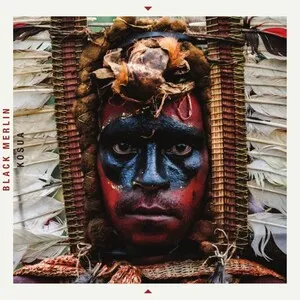

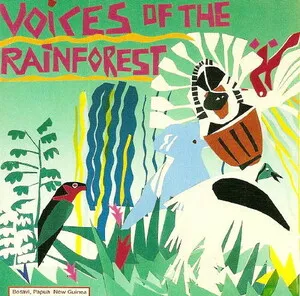

Papuan folk aesthetics inform regional popular and liturgical music, as well as international collaborations. Festival circuits and recordings present Asmat drumming, highland flute traditions, and Yospan (Biak/Yapen social dance music). While modernization and resource pressures challenge continuity, community transmission, schools, and archives help sustain repertoires. Today, Papuan folk’s timbres, polyrhythms, and communal vocals continue to shape Melanesian and Indonesian scenes and appear in worldbeat and world-fusion settings.