Your digging level

Description

Oromo music refers to the traditional and modern musical expressions of the Oromo people, the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, with communities also in Kenya. It encompasses ceremonial songs tied to the Gadaa socio-political system, work songs, lullabies, and vibrant dance music such as Sirba, as well as a contemporary pop stream that blends Oromo melodies with modern production.

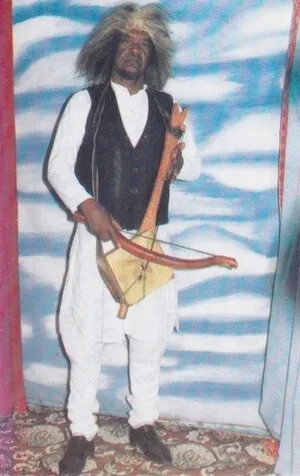

Musically, Oromo songs often use pentatonic scales common to wider Ethiopian traditions, cyclical ostinatos, call-and-response singing, and expressive vocal ornamentation. Core acoustic instruments include the krar (lyre), masenqo (one-string fiddle), washint (end-blown flute), and various drums (kebero), while modern acts incorporate guitar, keyboards, bass, drum kits, and programmed beats. Lyrically, performances in Afaan Oromo explore love, landscape, identity, social justice, and resilience, and they have frequently served as a vehicle for cultural affirmation and political commentary.

History

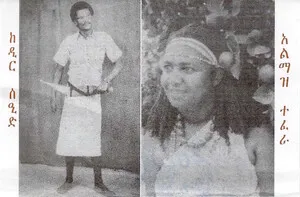

Oromo musical traditions predate written records, developing in close relation to the Gadaa system and community life across Oromia. Ritual songs, praise chants, and dances such as Sirba and Shagoyee structured social gatherings, rites of passage, harvest celebrations, and communal decision-making. Performance relied on vocals with ululation, handclaps, and local instruments like krar, masenqo, washint, and drums, with melodies typically pentatonic and rhythmically propulsive.

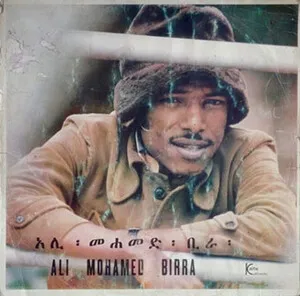

With urbanization and radio in the mid‑20th century, Oromo music moved onto stages and recordings. In the 1960s–70s, Ali Birra became a foundational figure, crafting popular songs in Afaan Oromo that fused traditional melodies with guitar- and horn-led urban arrangements influenced by ethio-jazz and regional pop. Despite periods of censorship and political pressure—especially during the Derg era—Oromo artists sustained and modernized the repertoire, embedding cultural pride within accessible pop formats.

The liberalization of media and the cassette economy in the 1990s enabled wider circulation across Ethiopia and the Oromo diaspora. Artists expanded arrangements with keyboards, drum machines, and reggae- or afrobeat-inflected rhythms while preserving traditional song forms and dance grooves like Sirba. Live bands and VCR/DVD markets grew, and Oromo music festivals emerged as key sites for cultural exchange.

In the streaming and social media era, Oromo music attained unprecedented visibility. Artists used YouTube and digital platforms to reach global audiences, fuse genres (afropop, reggae, hip hop) with Oromo scales and rhythms, and address themes of identity and social change. The life and work of Hachalu Hundessa epitomized the genre’s role in cultural expression and civic discourse, further cementing Oromo music as a vital voice within Ethiopian and East African popular culture.