Your digging level

Description

Muziki wa dansi is a Tanzanian big‑band dance music tradition that blossomed in the post‑colonial era. The name literally means "dance music" in Swahili, and the style is built for social dancing in clubs, union halls, and open‑air stages.

Musically, it blends Congolese rumba/soukous guitar interplay and Cuban son grooves with coastal taarab melodies, horn riffs, and a steady 4/4 backbeat. Bands typically feature multiple guitars (rhythm, mi‑solo/lead, and bass), a horn section, drum kit with auxiliary percussion (congas, shakers, cowbell), and call‑and‑response vocals in Swahili.

A hallmark of the genre is the use of mitindo (band‑signature dance styles/rhythmic patterns) and extended sebene‑style instrumental vamps that build energy for the dancefloor. Lyrics often mix romance, everyday life, social advice, and subtle political commentary, reflecting the culture of Ujamaa‑era Tanzania.

History

Muziki wa dansi emerged in urban Tanzania (then Tanganyika) in the 1950s, when amplified "jazz" dance bands (jazz here meaning dance band, not American modern jazz) began adapting Cuban son and Congolese rumba to local tastes. Early ensembles drew on coastal taarab melodic sensibilities and brass band instrumentation from colonial and missionary settings.

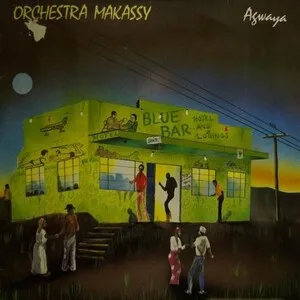

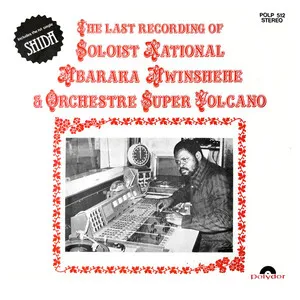

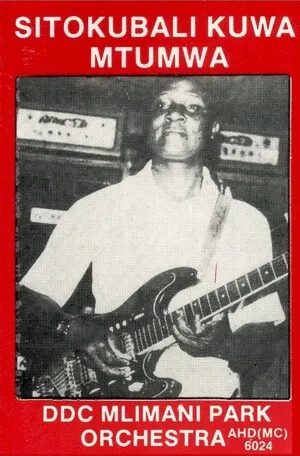

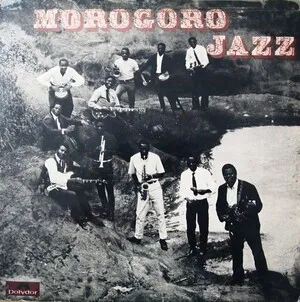

After independence, the Ujamaa period fostered a rich dance‑band ecosystem. Trade unions, parastatals, and city councils often sponsored groups, which enabled large line‑ups with horns and multiple guitars. Bands developed branded mitindo (signature rhythms/dance steps), fueling healthy rivalries and weekly dance events. Extended sebene sections, interlocking guitar lines, and Swahili call‑and‑response vocals defined the sound. Seminal bands such as Morogoro Jazz, Jamhuri Jazz, NUTA/Msondo Ngoma, Vijana Jazz, Orchestra Maquis Original, DDC Mlimani Park, and Orchestra Safari Sound dominated radio and dance halls.

From the 1990s, market liberalization and media shifts increased competition from imported soukous and emerging urban pop (later dubbed bongo flava). Some bands rebranded or streamlined; others dissolved. Veteran musicians (including Congolese‑born leaders active in Dar es Salaam) kept the style vibrant, while recordings circulated regionally.

Archival reissues and renewed domestic pride have spotlighted the genre’s historical importance. Muziki wa dansi’s band model, interlocking guitar language, and Swahili songwriting continue to inform contemporary Tanzanian styles, and its dance‑band ethos lives on through legacy groups, festival revivals, and younger musicians who borrow its grooves and stagecraft.