Levantine Arabic music refers to the musical traditions and popular styles that arose in the Levant (primarily Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Jordan). It blends urban maqām-based art song, rural dance repertories such as dabke, and modern pop production, all articulated in Levantine Arabic dialects.

The style is defined by modal melodies (maqāmāt like Bayātī, Ḥijāz, Rāst, Kurd), intricate vocal ornamentation, and cyclical rhythmic patterns (iqā‘āt) such as maqsūm (4/4), malfūf (2/4), and various 6/8 dabke feels. Core timbres come from the ‘ūd, qānūn, nāy, buzuq, mijwīz, riqq, and darbuka, often paired with violins and, in modern contexts, keyboards, drum machines, and sampled percussion. Lyrically, songs center on love, longing, memory of place, and social life, ranging from intimate ballads and muwashshaḥat/qaṣīda settings to festive wedding songs.

From the mid‑20th century onward, Beirut and Damascus became key hubs, with composers and arrangers modernizing orchestration while keeping maqām-centered melody and Levantine dance grooves intact. The result is a versatile spectrum—from tarab-inflected classics to sleek pop-dabke and indie fusions—that remains central to weddings, festivals, and radio across the Arab world and its diaspora.

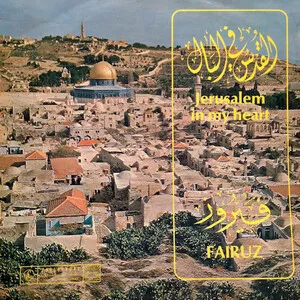

Levantine music draws on centuries of urban art song and devotional repertories centered in Aleppo, Damascus, Beirut, and Jerusalem. Modal (maqām) practice, Ottoman-era court aesthetics, and Syrian-Andalusian forms like the muwashshaḥ shaped the region’s sung poetry and improvisation (taqsīm, mawwāl). Parallel rural repertoires, including dabke dance songs and shepherd tunes on mijwīz and buzuq, fed a shared musical vocabulary.

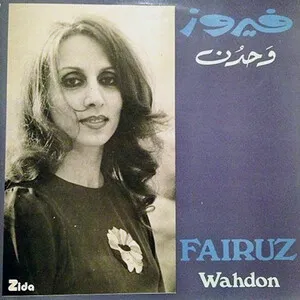

With the rise of radio, records, and festivals, Lebanon and Syria emerged as production centers. The Rahbani Brothers and Fairuz modernized Levantine song with orchestral arrangements while retaining maqām logic and Levantine prosody. Stars such as Wadih El Safi and Sabah codified the vocal style and turned dabke rhythms into concert staples. Baalbek and other festivals, alongside film and TV, circulated the sound across the Arab world.

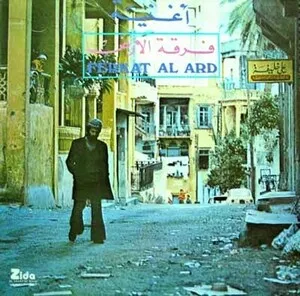

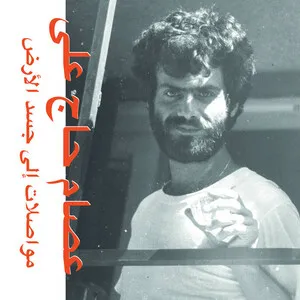

Civil wars and migration dispersed musicians, but studios in Beirut continued to innovate. Synthesizers and drum machines entered the palette, yielding pop‑dabke and jazz-inflected protest and theatre songs (notably via Ziad Rahbani). Syrian and Palestinian artists sustained tarab traditions while experimenting with lighter pop formats tailored to cassette culture and satellite TV.

Beirut’s labels and pan‑Arab TV turned Levantine Arabic into a lingua franca of regional pop (Nancy Ajram, Ragheb Alama, Assala). Parallel indie and fusion scenes (e.g., Marcel Khalife’s contemporary classical/folk projects, Omar Souleyman’s electro‑dabke) pushed the sound into festivals and clubs globally. Streaming and social media amplified wedding dabke trends, nostalgic ballads, and genre hybrids with EDM, hip hop, and alternative rock—all while the core maqām/iqa‘ grammar remains recognizable.