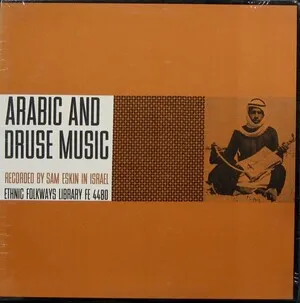

Druze music refers to the vocal and instrumental practices of the Druze ethno‑religious community of the Levant. It encompasses two complementary spheres: a sacred, largely a cappella chant tradition tied to Druze theology and communal ritual, and a public/folkloric repertoire shared with wider Levantine village culture.

In religious contexts (within khalwa prayer houses), music is principally vocal: unison or lightly heterophonic chanting of sacred texts, delivered in Arabic using maqām-based melodic language and restrained ornamentation. Instruments are traditionally avoided in devotional settings, underscoring sobriety, contemplation, and ethical instruction.

In public life—weddings, seasonal feasts, and village gatherings—Druze repertoire overlaps with broader Levantine folk song (mijana, ʿatāba, dalouna) and dance (dabke). Here, the oud, buzuq, mijwiz/ney, riqq, daff, and darbuka support strophic, call‑and‑response singing and energetic circle dancing. Themes revolve around honor, hospitality, courage, love, and attachment to the mountains.

The Druze faith crystallized in the early 11th century in the Levant, and a devotional chant practice developed alongside its theological texts and communal norms. Early musical usage favored unaccompanied, text‑centered recitation in Arabic, drawing on shared Near Eastern modal practice (maqām) while maintaining a discreet, inward-focused ethos within khalwa spaces.

Under Ottoman rule, Druze mountain communities in Mount Lebanon and Jabal al-Druze (al-Suwayda) maintained distinct ritual music while participating in regional folk culture. Village celebrations adopted popular Levantine poetic-sung forms—zajal improvisation, ʿatāba/mijana strophic songs, and dabke dance—performed with oud, buzuq, and reed pipes (mijwiz/ney). The sacred-profaneduality remained clear: devotional chant stayed largely a cappella and private, while public repertories thrived communally.

Mass media amplified Druze-connected artists and regional styles. Syrian‑Egyptian Druze stars such as Farid al‑Atrash and Asmahan helped modernize and popularize Levantine and Arabic classical idioms on stage and screen, even as village ensembles preserved local dance songs and poetic duels. In Syria’s Jabal al‑Druze and Lebanon’s Chouf, folklore troupes and zajal circles kept communal performance vibrant at weddings and festivals.

Today, Druze sacred chant continues in private settings, transmitted orally among community elders and chanters. Public-facing practice thrives at lifecycle events and cultural festivals across Lebanon, Syria, Israel/Palestine (Galilee, Carmel, Golan), and the diaspora. Folkloric groups emphasize dabke suites, call-and-response singing, and maqām‑based instrumentals, while Druze heritage also persists through notable individual artists who bridge folk, classical, and socially conscious song.