Hmong folk music is the traditional musical expression of the Hmong (Miao) people, whose communities historically lived in the mountainous regions of southern China and later migrated across mainland Southeast Asia. It centers on an oral, community-based practice linked to ritual, storytelling, courtship, and seasonal festivities.

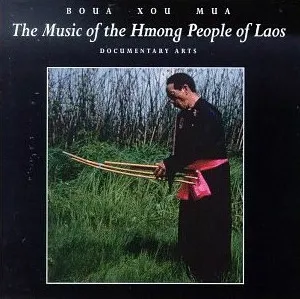

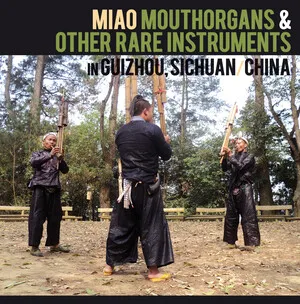

Core to the sound is the qeej (a multi-pipe free-reed bamboo instrument), whose melodies encode tones of the Hmong language to recite poetic texts, especially in funerary rites and ceremonial contexts. Vocal genres such as kwv txhiaj (improvised sung poetry) convey complex narratives, moral teachings, and personal sentiments with intricate melodic contours. Supporting instruments include the ncas (jaw’s harp), raj (flutes), and various drums and gongs.

Musically, Hmong folk practice favors modal/pentatonic pitch collections, flexible rhythm shaped by speech-tone prosody, and a close marriage of language and melody. The result is a highly expressive, text-forward tradition that carries cultural memory, social values, and spiritual meaning.

Hmong folk music developed within the Hmong communities of southern China, with roots stretching back many centuries as part of a broader Sinosphere of tonal, ritual, and poetic performance. The practice is deeply interwoven with language, clan identity, and animist spiritual beliefs. Its most emblematic instrument, the qeej, likely co-evolved alongside other mainland Southeast Asian free-reed aerophones, but took on uniquely Hmong linguistic and ritual functions.

From the 1700s through the 1800s, successive waves of migration brought Hmong communities into present-day Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar. These movements localized the music further: courtship songs (kwv txhiaj) flourished in New Year festivals; funerary qeej performances codified regional ceremonial repertoires; and instrument-building practices adapted to available materials while preserving linguistic encoding.

In the 20th century, ethnographers and broadcasters began to record Hmong musical practices, creating early archives. Post-1975 diaspora dispersals to countries such as the United States, France, and Australia introduced new performance contexts (community centers, multicultural festivals), while cassette culture and later VCD/DVDs circulated traditional songs among transnational families.

Today, Hmong folk music persists in ritual life (especially funerals and New Year celebrations), in staged cultural showcases, and in educational programs. Diaspora communities support preservation through qeej clubs, youth ensembles, and cultural centers. While contemporary Hmong pop draws on global sounds, traditional vocal poetry and qeej ceremonies remain vital pillars of communal identity and intergenerational transmission.