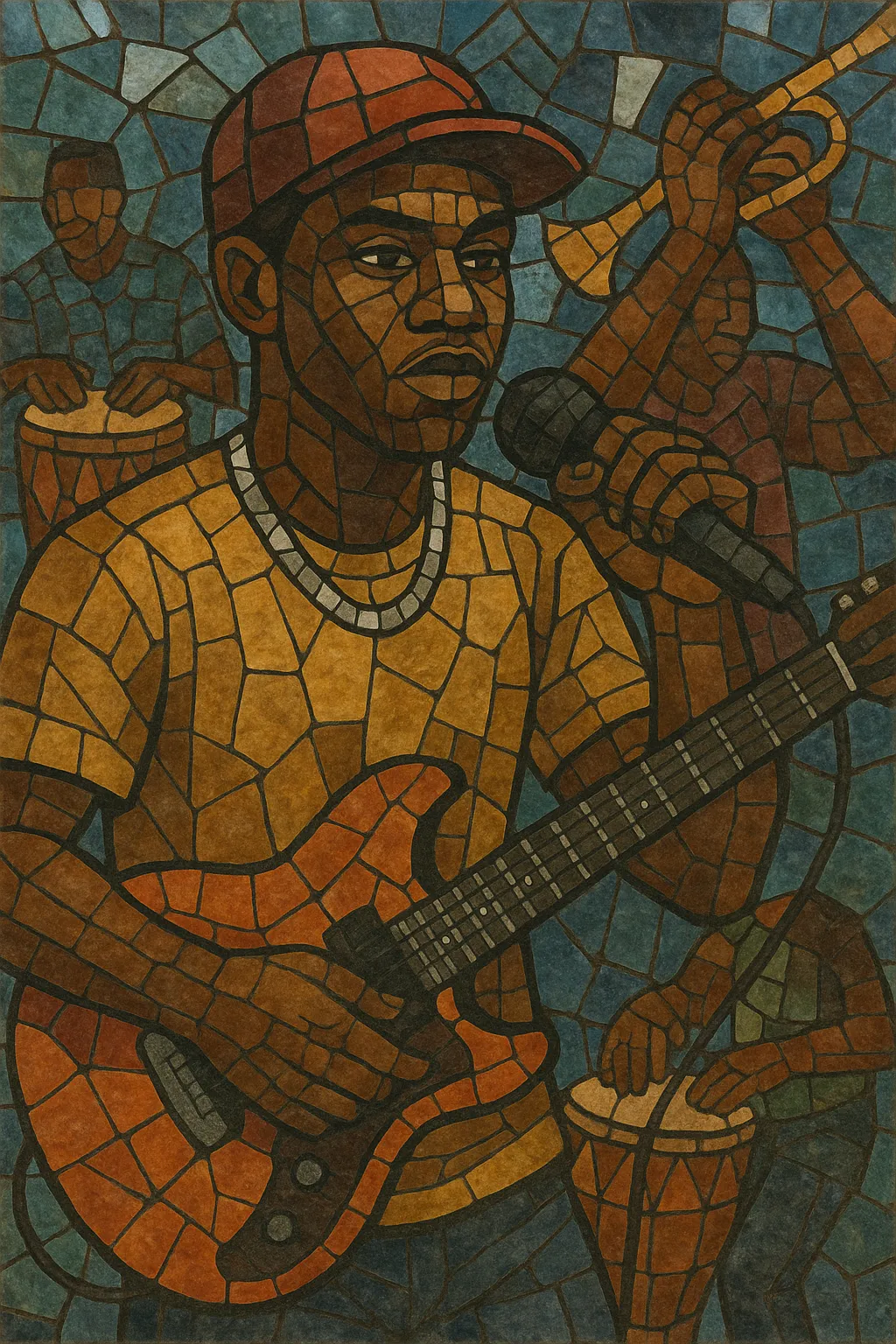

Hiplife is a Ghanaian popular music style that fuses the melodic guitar lines, horn riffs, and danceable grooves of highlife with the beats, rhyme schemes, and production aesthetics of hip hop and R&B.

Performed largely in local languages such as Twi, Ga, and Ewe alongside Ghanaian Pidgin English, hiplife balances storytelling rap verses with catchy, highlife-inspired sung hooks. Its rhythms often blend programmed hip hop drums with live West African percussion (e.g., kpanlogo), producing a feel that is both club-ready and rooted in Ghana’s musical heritage.

The genre became the voice of urban youth culture in Ghana from the late 1990s onward, providing a platform for social commentary, humor, and everyday narratives, while also laying groundwork for later West African pop movements.

Hiplife emerged in Ghana during the 1990s as artists began rapping over highlife-derived instrumentals. Often cited as a key pioneer, Reggie Rockstone returned to Accra from London and popularized the fusion by combining hip hop flows with highlife grooves and Ghanaian languages. Early producers such as Zapp Mallet, Panji Anoff, and Jay Q helped codify the sound with a mix of sampled highlife textures, live guitars, horns, and boom‑bap drum programming.

Through the early 2000s, artists like Obrafour, Lord Kenya, Tic Tac (now Tic), and VIP took hiplife nationwide, while producers like Appietus and Hammer (The Last Two) developed instantly recognizable beat signatures. The scene embraced both party anthems and reflective storytelling, and collaborations between rappers and highlife vocalists became a hallmark of the style.

As Afrobeats rose across West Africa, hiplife’s melodic hooks and percussion-forward production fed into the new pan‑regional pop sound. In Ghana, hiplife interplayed with dance styles and subgenres such as azonto, and later intersected with drill (asakaa), while artists like Sarkodie bridged classic hiplife techniques with contemporary trap, Afrobeats, and pop.

Hiplife solidified the template for rapping in local Ghanaian languages over homegrown rhythms, inspiring subsequent Ghanaian hip hop movements and shaping the broader West African pop landscape. Its emphasis on hybrid production and linguistic identity remains a defining influence.