Your digging level

Description

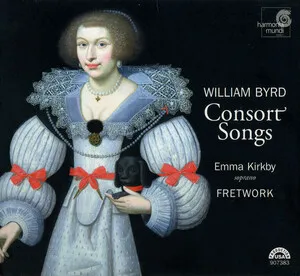

Elizabethan song refers primarily to the English solo song with lute (often called the ayre), and the related consort song for voice with a viol consort, cultivated during the reign of Elizabeth I. Typically strophic and text-led, these songs set courtly, pastoral, or amorous poetry in clear, singable melodies supported by contrapuntal or chordal lute accompaniments.

Hallmarks include finely balanced prosody, vivid word-painting, and modal harmony (often Aeolian, Dorian, and Mixolydian) gradually shading toward early tonal cadences. The style sits between popular and learned traditions: it borrows memorable tunefulness from ballad and dance idioms while deploying Renaissance contrapuntal craft.

Songs were circulated in printed partbooks and lute tablature, intended for both courtly performance and domestic music-making. The repertory remains prized for its intimate expressivity, rhetorical clarity, and refined yet approachable musical language.

History

Elizabethan song emerged in late 16th‑century England within the broader Renaissance vocal culture. The import of Italian madrigals (notably via Musica transalpina, 1588) stimulated English interest in expressive text-setting and elegant counterpoint, while native ballad and dance traditions supplied memorable melodic shapes and strophic designs. Courtly and domestic music-making created demand for refined yet performable repertoire.

During the 1590s–early 1600s, printed songbooks by John Dowland, Thomas Campion, Philip Rosseter, Thomas Morley, Robert Jones, Thomas Ford, and others codified the ayre for solo voice and lute, alongside consort songs for voice with viol ensemble. These collections showcase:

• Poised melodies closely aligned to English poetic accent. • Modal harmony with clear cadential formulas and occasional expressive cross-relations (“English false relations”). • Word-painting and rhetorical devices learned from madrigal practice, applied to more intimate solo textures.Songs appeared in mixed notation (voice part in staff notation, lute in French tablature), enabling flexible forces: solo singer with lutenist, self-accompanied singer, or ensemble arrangements with viols. Domestic music-making, collegiate and court circles, and the theatrical milieu (including songs associated with plays) fostered wide dissemination.

Elizabethan song established a durable English art-song ideal—text intelligibility, lyrical restraint, and chamber intimacy—that influenced later Baroque song traditions and, over centuries, fed the English-language art song lineage. Its lute-derived textures and modal color also informed modern revivals and inspired 20th‑century “folk baroque” fingerstyle and early-music performance movements.