Chilean music is an umbrella term for the diverse musical practices that developed in Chile, spanning rural folk traditions, urban popular music, and modern hybrid scenes. Its core pillars include the cueca (the national dance), the tonada chilena, and Andean-influenced folk, alongside later movements such as Nueva Canción Chilena, rock en español, cumbia chilena, indie pop/rock, hip hop, reggaetón, and experimental scenes.

Forged at the crossroads of Indigenous (Mapuche and Andean), Iberian (Spanish folk and salon forms), and Afro-diasporic currents (via the zamacueca), Chilean music combines characteristic strummed guitars, the guitarrón chileno and paya traditions, Andean winds (quena, zampoña), cueca’s stamping rhythms and pandero hand drum, and poetic, socially conscious lyricism. In the 20th century it became a continental reference through Nueva Canción’s politically engaged songwriting and later through rock, pop, and urban genres that placed Chile on the global map.

Chilean music as a national tradition coalesced in the mid-1800s when the zamacueca—an Afro-Iberian couple dance circulating along the Pacific coast—evolved locally into the cueca. Rural and urban salons incorporated Spanish folk forms (fandango-derived dances, waltz, polka), while Indigenous Mapuche and Andean practices contributed modalities, instruments (trutruka, quena, zampoña), and vocal styles. The tonada chilena crystallized as a lyrical song form distinct from the cueca’s dance character.

Recording, radio, and state cultural projects helped standardize música típica chilena (the canonical repertoire of cuecas, tonadas, and rural song). Urban bolero and salon influences intertwined with local forms, and the guitarrón chileno and paya (improvised décima poetry) kept living oral traditions at the fore.

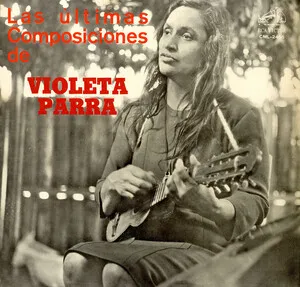

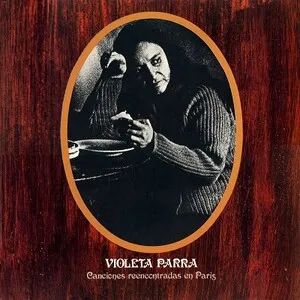

Artists such as Violeta Parra and Víctor Jara modernized folk idioms with poetic, socially engaged lyrics, inspiring Nueva Canción Chilena. Groups like Inti-Illimani, Quilapayún, and Illapu integrated Andean instrumentation and pan-Latin repertoire. After the 1973 coup, exile networks spread Chilean music internationally; the movement became a continental touchstone for politically conscious songwriting.

Despite censorship, bands like Los Prisioneros catalyzed Chile’s role in rock en español. The 1990s–2000s brought eclectic fusions: Los Tres and Los Jaivas bridged folk, rock, and psychedelia; pop and singer-songwriter currents flourished; hip hop and electronica scenes emerged alongside a revitalized cumbia chilena.

A vibrant indie ecosystem (e.g., Gepe, Dënver), globally recognized voices (Mon Laferte, Ana Tijoux), experimental producers, and urban styles (trap, reggaetón, and neoperreo) expanded Chile’s international footprint. Festivals, digital platforms, and archival revivals continue to connect historical folk with contemporary innovation.