Música típica chilena is a stylized, urban presentation of Chile’s rural folk traditions that coalesced in the early radio era. It highlights huaso (Chilean cowboy) imagery, close-harmony vocal ensembles, and dance-song forms such as the cueca and the tonada.

Typical instrumentation includes nylon-string guitars, guitarrón chileno, Chilean harp, accordion (especially in southern repertoires), pandero cuequero, and light percussion. Songs frequently emphasize clear melodies, major-key harmonies (I–IV–V with occasional secondary dominants), and danceable rhythms with characteristic hemiola interplay between 6/8 and 3/4 in cueca forms.

Lyrically, the repertoire celebrates rural life, love, nature, and patriotism, often using coplas and décimas. The style became a national symbol through polished stage and radio performances by huaso quartets and mixed ensembles, especially around national festivities.

Although its roots lie in 19th‑century rural dances and song forms (notably cueca and tonada), música típica chilena took its modern, polished form in the early 20th century with the rise of urban theaters, phonograph records, and radio. By the 1930s, professional huaso ensembles brought rural repertories to city audiences, standardizing vocal harmonies, arrangements, and stage image.

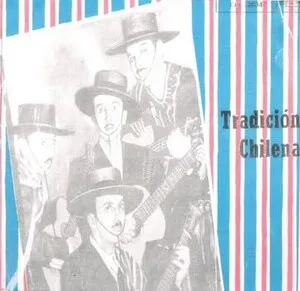

The style reached mass popularity via national radio, film, and festivals. Groups such as Los Cuatro Huasos and Los Huasos Quincheros established the model of the huaso quartet: tight three‑ and four‑part harmonies, guitars and harp or accordion, and a repertoire centered on cuecas, tonadas, and valses. This era canonized many songs that became staples of Chile’s patriotic celebrations.

From the late 1950s and 1960s, research‑performers like Margot Loyola and Silvia Infantas deepened ties to regional traditions, while the "neofolklore" and later Nueva Canción movements drew on típica’s song forms but pushed toward social commentary and broader Andean instrumentation. Música típica remained popular in media and at fiestas patrias, even as more socially engaged folk currents grew.

Successive generations of huaso ensembles (e.g., Los Huasos de San Javier) kept the repertoire active. Cultural policies, folklore programs, and local peñas helped maintain the practice in schools and communities. Today, música típica chilena continues as a living emblem of national identity, coexisting with scholarly folklore revivals and contemporary fusions.