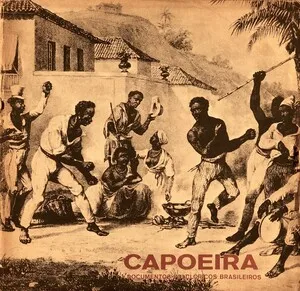

Capoeira music is the Afro‑Brazilian musical tradition that accompanies the capoeira game, guiding tempo, energy, ritual cues, and dialogue between players in the roda (circle).

It centers on a small percussion ensemble led by the berimbau — a single‑string musical bow with gourd resonator — supported by pandeiro (frame drum), atabaque (tall drum), agogô (double bell), and reco‑reco (scraper). Singing is predominantly in Portuguese and follows call‑and‑response formats.

Songs are grouped into forms such as ladainha (solo invocation or litany), louvação (praise), and corrido (call‑and‑response chants), while standardized berimbau toques (rhythmic patterns) like Angola, São Bento Pequeno/Grande, Iúna, and Cavalaria set the character of the game from slow, strategic play to fast, acrobatic exchanges.

Capoeira music emerged in Bahia, Brazil, among enslaved and Afro‑descendant communities who fused Central and West African musical bow traditions, ritual drumming, and Portuguese verse into a distinct practice. By the 1800s, the berimbau had become closely associated with capoeira, and singing in call‑and‑response or narrative forms provided coded messages, praise, and social commentary within the roda.

In the early 1900s, public rodas in Salvador’s markets and neighborhoods (e.g., at the Roda da Liberdade) helped stabilize instrumentation: berimbau(s), pandeiro, atabaque, agogô, and reco‑reco. Masters such as Mestre Waldemar led influential rodas where carving and tuning berimbaus and leading traditional ladainhas and corridos became an art in itself.

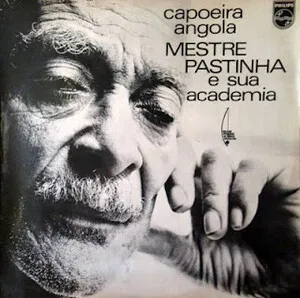

In the 1930s, Mestre Bimba founded Capoeira Regional, systematizing training and repertory of toques, placing the berimbau at the musical center, and introducing faster, athletic games like São Bento Grande. Mestre Pastinha codified Capoeira Angola, emphasizing slower, strategic play to the toque Angola and preserving older song forms and etiquette. Early recordings by mestres such as Mestre Traíra and documentation around Pastinha and Waldemar disseminated classic ladainhas and corridos.

From the 1970s onward, teachers including Mestre Acordeon and Mestre João Grande carried capoeira and its music abroad, publishing songbooks and making seminal recordings. The 1980s revival in Salvador led by Mestre Moraes (GCAP) reinforced traditional Angola repertory and ritual. Capoeira music entered world‑music circuits, influencing Brazilian popular music and appearing in film and stage productions.

Today, capoeira music is taught worldwide. While many groups preserve canonical toques and song forms, others compose new corridos and ladainhas, experiment with harmony, or integrate amplified berimbau and studio production. Across styles, the berimbau battery, call‑and‑response singing, and the functional link between musical toque and players’ jogo remain the genre’s core.

Use a berimbau bateria as the core: at least one berimbau gunga (low), one médio (middle), and one viola (high, improvising), plus pandeiro, atabaque, agogô, and reco‑reco. The gunga sets the pulse, the médio locks the pattern, and the viola ornaments.

Choose a toque that matches the intended game: Angola (slow, grounded, strategic), São Bento Pequeno (medium, playful), São Bento Grande (fast, acrobatic), Iúna (ceremonial, for advanced players), or Cavalaria (historical warning rhythm). Keep the groove in 2/4 or 4/4 with strong syncopation and off‑beat accents.

Structure the roda with a ladainha (solo invocation by the leading singer), followed by a louvação (short praise section), then corridos (call‑and‑response chants). Write concise, memorable lines in Portuguese, using repetition and proverbial imagery. Themes include history, mestres, malícia (cunning), community, and observations about the game. Encourage group chorus to answer the leader clearly and rhythmically.

Melodies are narrow‑ranged, modal, and rhythm‑driven, often centered around the berimbau’s two main pitches (open string and pressed note) with the caxixi adding articulation. Harmony is minimal; if using guitar or additional instruments, keep chords sparse (I–IV–V or drone‑based) so they do not compete with the berimbau.

Begin with the ladainha over a steady berimbau gunga. Add percussion gradually, invite clapping (palmas), then transition to corridos to open the game. Adjust dynamics and tempo in real time to cue entrances, exits, and the character of play. Maintain clear call‑and‑response and avoid over‑arrangement; function guides form.

Tune berimbaus carefully (string tension, gourd position) and balance the gunga prominently in the mix. Mic the atabaque for warmth, keep pandeiro crisp, and capture group vocals with a room mic to preserve communal energy. Favor live takes to retain the roda’s spontaneity.