Canarian folk music is the traditional music of the Canary Islands (Spain), shaped by centuries of exchange between Iberian settlers, Indigenous Guanche/Amazigh roots, and the Atlantic routes connecting the archipelago with the Caribbean and Latin America.

Its sound is instantly recognizable by the bright, chiming timple (a small 5‑string lute) alongside Spanish guitars, laúd and bandurria, and island-specific percussion such as chácaras (large castanets from La Gomera and El Hierro) and the tambor gomero. Singing is often ornamented and lyrical, carrying décima poetry and coplas about seafaring, emigration, love, and island life.

Core song‑dance forms include the lively isa (often in triple meter), the slow and expressive folía, the malagueñas canarias (a local take linked to Andalusian practice), the tajaraste (driven by drum and chácaras), the sorondongo, and the polca majorera. Performances thrive in romerías (processional feasts), bailes de taifa (community dances), and informal parrandas (song gatherings), where call‑and‑response refrains invite collective participation.

After the Castilian conquest in the late 1400s, Iberian ballad and dance traditions (romances, seguidillas, fandangos, folías) mixed with surviving Indigenous Guanche/Amazigh elements. By the 18th century, a distinct island sound coalesced around local string ensembles and the emergence of the timple, especially on Lanzarote and Fuerteventura.

Intense migration and trade with Cuba, Venezuela, and Puerto Rico created a two‑way musical current. Islanders absorbed habanera rhythms, bolero lyricism, and criollo accompaniment styles; in turn, Canarian settlers contributed to the growth of eastern Venezuelan and Cuban rural song practices. Local variants such as the malagueñas canarias and isas took stable form in this period.

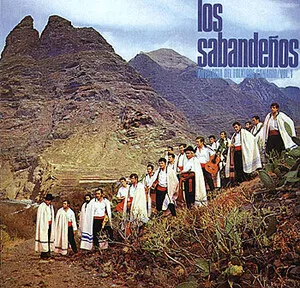

From the 1950s onward, recording and broadcasting spread island repertoires beyond local fiestas. In the late 1960s–70s, ensembles like Los Sabandeños and Los Gofiones professionalized the genre, creating choral‑string arrangements that balanced authenticity with concert presentation. Folklore groups, dance troupes, and festivals systematized repertoires (isa, folía, tajaraste, sorondongo), while community parrandas kept participatory traditions alive.

Modern artists and timple virtuosos expanded technique and harmony, collaborating with Latin and world‑music players while preserving core rhythms and dances. Today, Canarian folk thrives in romerías and bailes de taifa, on international stages, and in crossover projects that foreground the timple, island percussion, and poetic décimas.