Andalusian folk music refers to the traditional song and dance repertories of Andalusia (southern Spain), including sevillanas, verdiales, fandangos de Huelva, and related copla-andaluza song forms.

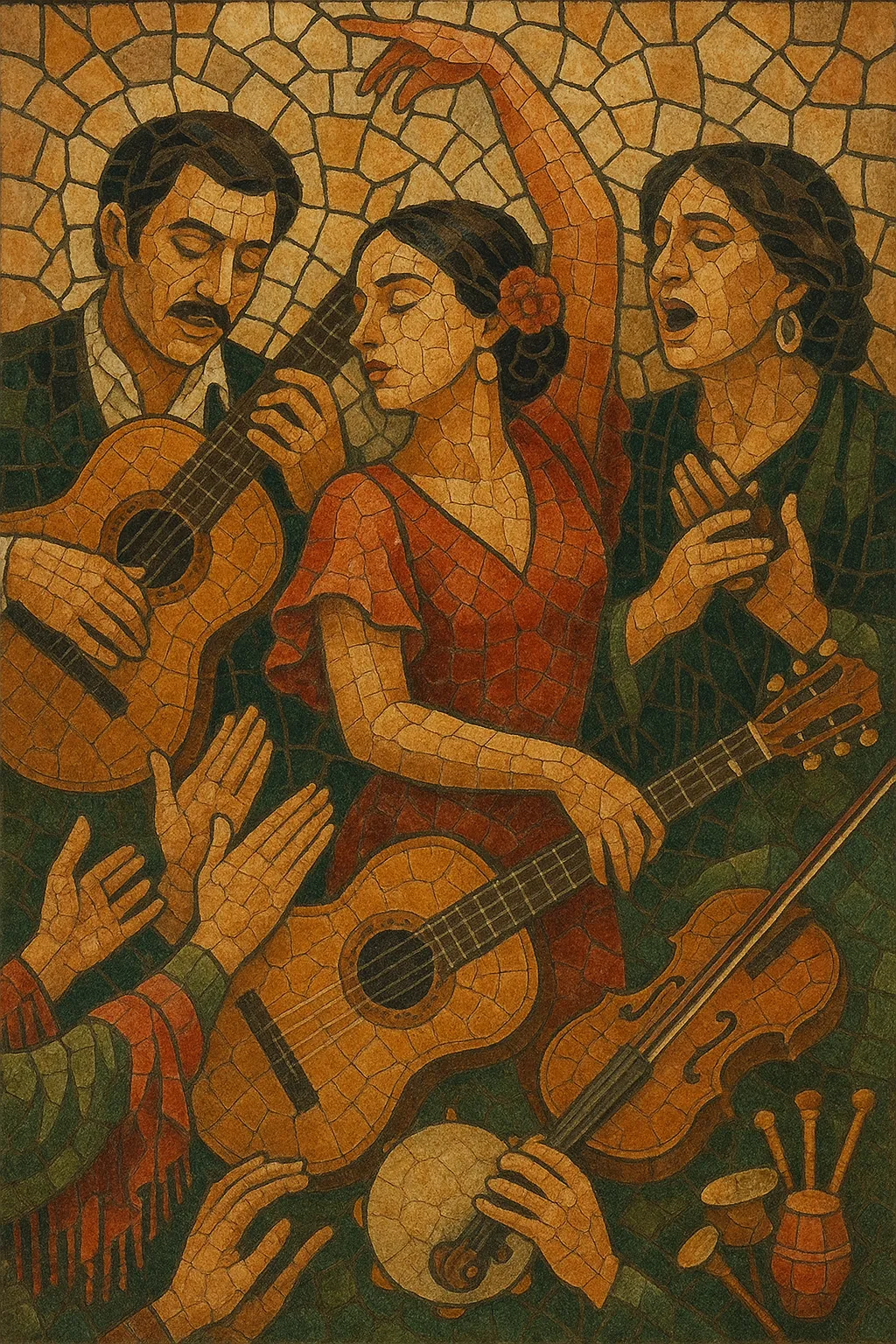

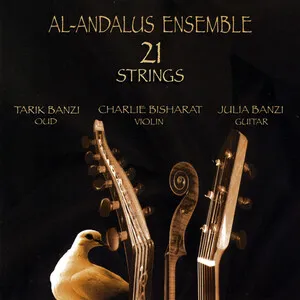

It blends medieval Andalusí (Arab-Andalusian) modal color and poetic strophic forms with Iberian dance-song traditions, creating music that is both festive and lyrical. Typical features include melismatic vocals, the Andalusian cadence (iv–III–II–I in the Phrygian area), palmas (handclapping), castanets, and guitars—alongside regional ensembles like the verdiales pandas (with violin, guitars, pandero/tambourine, cymbals, and bandurria/lute).

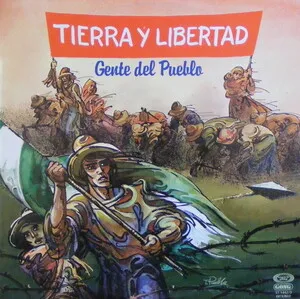

Andalusian folk music crystallized in the 19th century from much older layers: medieval Andalusí (Arab-Andalusian) music, Iberian ballad traditions, and local dance-songs. Strophic poetic forms like the zajal and muwashshah informed Andalusian lyricism, while village fiestas and religious/calendrical celebrations sustained local dance repertoires. Early forms of fandango and seguidilla fed directly into Andalusian variants such as fandangos de Huelva and sevillanas.

By the 1800s, sevillanas were widely codified as a couple-dance with four coplas, and verdiales thrived around Málaga as a vibrant fiddle-led tradition. The guitar gained prominence, accompanying octosyllabic coplas with strong hemiola interplay (3/4 and 6/8). The poetic character—often bittersweet, nostalgic, or festive—aligned Andalusian folk with emerging popular-theater circuits and café cantantes, where parallel flamenco developments also unfolded.

Radio, records, and film amplified sevillanas and copla-andaluza, fostering celebrated interpreters and large ensembles. Local brotherhoods and pilgrimages (notably the Romería del Rocío) reinforced community performance contexts and spawned influential sevillanas groups. Meanwhile, rural panda de verdiales traditions preserved older instrumentation and performance practice.

Andalusian folk remains central to regional identity—taught in schools, danced at ferias, and recorded by both traditional ensembles and crossover artists. It continues to inform contemporary fusions (flamenco pop, nuevo flamenco, rock andaluz), while local peñas and pandas safeguard historical styles, repertoires, and performance etiquette.