Blue‑eyed soul is a style of soul music performed primarily by white artists who adopt the vocal inflections, rhythmic feel, and arranging language of classic R&B and gospel. Emerging in the 1960s in the United States and the United Kingdom, it bridges Motown polish and Southern soul grit with pop‑oriented songwriting.

Typical recordings feature impassioned lead vocals, stacked harmonies, backbeat‑driven rhythm sections, Hammond organ or electric piano, punchy horn lines, and occasionally lush strings. The result is radio‑friendly soul that retains emotional intensity while appealing to mainstream pop audiences.

The label “blue‑eyed soul” has been used descriptively and sometimes controversially; it points to a sound rather than identity. Historically, however, it referred to white performers making music in a soul idiom.

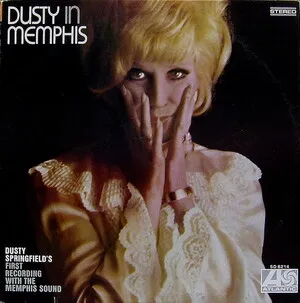

The term “blue‑eyed soul” came into use in the mid‑1960s to describe white performers who embodied the intensity and vocal style of African‑American soul. Early exemplars included The Righteous Brothers in the U.S. and Dusty Springfield and The Spencer Davis Group in the U.K. These artists drew heavily on Motown’s polished songwriting and Stax/Atlantic’s Southern soul grooves, often covering R&B hits while crafting original tunes with gospel‑derived harmonies and a strong backbeat.

Radio formats and integrated touring circuits helped the style cross over, and acts like The Rascals scored major hits that sat comfortably on both pop and R&B charts.

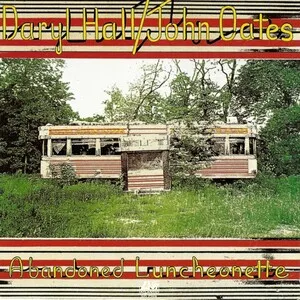

In the 1970s, blue‑eyed soul broadened into smoother, pop‑leaning territory. Hall & Oates, Boz Scaggs, and Michael McDonald (solo and with The Doobie Brothers) fused soul harmony with sophisticated pop production, laying foundations for soft rock and yacht rock. In the 1980s, Simply Red carried the torch in the U.K., pairing soulful vocals with glossy, radio‑ready arrangements.

Successive waves of revivalism kept the sound current. Artists such as Amy Winehouse and Adele revived vintage soul aesthetics with contemporary songwriting and production, reconnecting mainstream audiences to classic R&B timbres while maintaining pop accessibility. The style’s DNA also informed strands of pop soul and sophisti‑pop.

While the label can be contentious, it remains a shorthand for a specific blend of soul idioms delivered through pop frameworks. Its history underscores the deep influence of African‑American musical traditions on global pop and the enduring appeal of gospel‑inflected singing, rich harmonies, and groove‑centered arrangements.