Balochi music is the traditional and contemporary music of the Baloch people, spread across Pakistan’s Balochistan, southeastern Iran, and southwestern Afghanistan. It blends epic storytelling and devotional poetry with distinctive regional rhythms and modal melodies related to Persian and Gulf traditions.

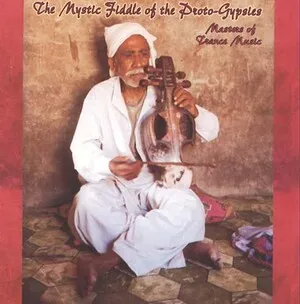

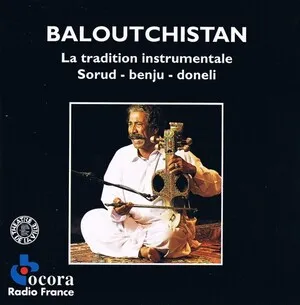

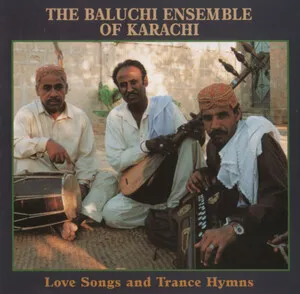

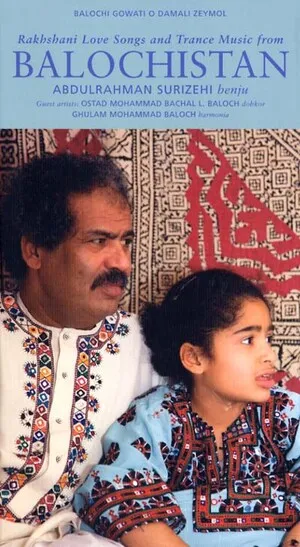

Its signature timbres come from the benju (a keyed zither often called the “Balochi banjo”), the bowed suroz/sorud, and the long‑necked lute tamburag, supported by hand percussion like dholak and dammam and accented with clapping patterns. Vocals are typically melismatic, with free‑flowing ornamentation and microtonal inflections.

Repertoire ranges from heroic ballads and love epics to wedding songs and trance‑like coastal dances (e.g., lewa/laywa). Modern artists increasingly fuse these elements with pop, rock, and hip hop production, bringing the Balochi language and aesthetics into global “world fusion” contexts.

Balochi music arises from the oral traditions of the Baloch people along ancient trade and migration routes linking the Iranian plateau, South Asia, and the Arabian Sea. The genre’s core functions historically included praise singing for tribal leaders, recounting epics of heroes and lovers, and ceremonial music for weddings, harvests, and communal rites.

By the late 19th to early 20th century, a distinct instrumental palette had crystallized: the benju (keyed zither) became a hallmark of Makran coastal ensembles, the suroz/sorud (bowed lute) carried plaintive melodic lines in inland regions, and the tamburag (long‑necked lute) provided drone and rhythmic ostinati. Percussion (dholak, dammam) and choral clapping support dance genres, especially along the coast where call‑and‑response and 6/8 lewa patterns reflect Gulf exchange.

With radio and later cassette culture, master performers and epic singers reached wider audiences across Pakistan and Iran. Modal practice remained close to Persian dastgāh sensibilities (e.g., shur, homayun), while lyrical themes balanced tribal history, love poetry, and devotional Sufi content. Migration to Karachi, Gwadar, Chabahar, and Gulf ports intensified cross‑regional influences and professionalized ensembles.

Since the 1990s, diaspora artists and local innovators have fused benju and suroz with electric bass, drum kit, and modern production. Television and studio platforms helped bring Balochi‑language songs to national and international audiences, seeding collaborations with pop, rock, and hip hop while preserving core melodic ornaments, dance meters, and poetic delivery.