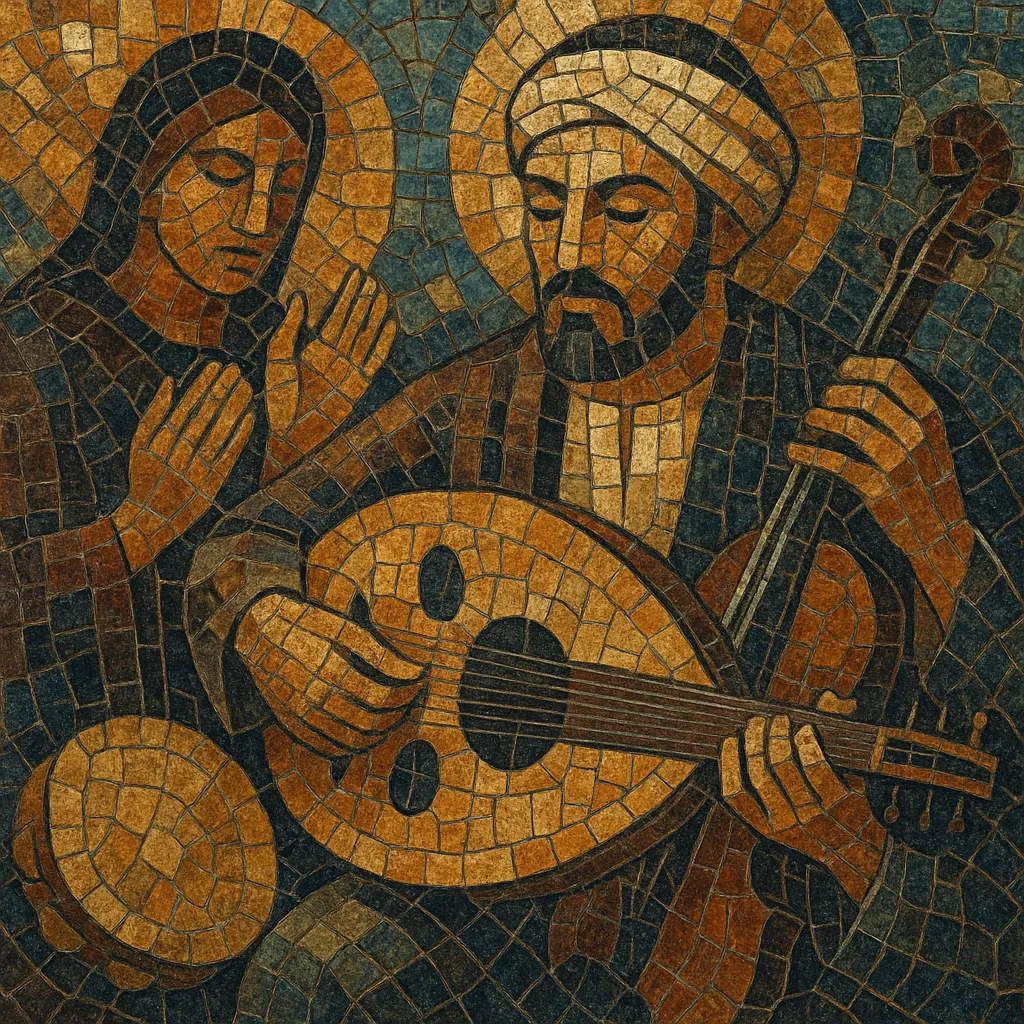

Sawt (Arabic: صوت) is an urban Gulf song tradition that crystallized in Kuwait and Bahrain at the turn of the 20th century. It is typically performed in intimate majlis settings by a lead singer accompanied by oud, the small frame drum mirwās, handclaps, and often violin.

Musically, sawt draws on the maqām system (modal scales such as Rast, Bayāt, and Ḥijāz), features short instrumental taqsīm (improvisations) and cyclic rhythms, and sets Arabic poetic couplets (ghazal and Nabati verse) to song. The performance balances refined modal melody with driving, syncopated Gulf handclap patterns, producing a sound that is both contemplative and dance-inducing.

Culturally, sawt became a hallmark of early 20th‑century port cities on the Persian/Arabian Gulf, reflecting Indian Ocean trade routes: Iraqi and Persian melodic aesthetics, local Bedouin/Najdi poetic practice, and lively social gatherings specific to the coastal Gulf.

Sawt emerged in the late 1800s in the coastal towns of today’s Kuwait and Bahrain. Early practitioners adapted courtly and urban Arab-Persian melodic practices to local majlis settings, accompanying Arabic poetry with oud and the small frame drum mirwās. The genre took shape amid Indian Ocean trade networks, absorbing Iraqi maqām nuances, Persian ornamentation, and local Najdi/Bedouin sung poetry.

By the 1920s–30s, sawt had a distinct repertoire and star performers. Pioneers such as Abdullah Al‑Faraj in Kuwait and Mohammed bin Faris in Bahrain formalized melodic-rhythmic formulas, introduced violin alongside oud, and established performance etiquette (opening taqsīm, alternating sung couplets and instrumental responses, coordinated clapping). Early recordings made in Basra, Baghdad, Bombay, and later on regional labels circulated the style widely across the Gulf.

Sawt became central to evening gatherings and festive occasions in port cities. Its lyrics favored love, longing, and wisdom, often in ghazal or Nabati meters. Modal practice emphasized expressive microtonal intonation, while the mirwās and coordinated handclaps created compelling rhythmic cycles in 2/4 and 6/8 feels.

Radio and state ensembles helped maintain the tradition through the mid‑20th century even as Khaliji popular music modernized. Contemporary custodians and folk ensembles in Bahrain and Kuwait keep the repertoire alive, and elements of sawt’s modal melody and rhythms have filtered into modern Khaliji and broader Arabic pop arrangements.