Altai music is the traditional music of the Altai peoples in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. It is marked by epic storytelling, overtone (throat) singing known locally as kai, and a timbre-first aesthetic that imitates the sounds of wind, rivers, birds, and horses.

Core instruments include the topshur (a two‑string plucked lute), the shoor (end‑blown flute), the khomus (Jew’s harp), and frame drums used in ritual and narrative contexts. Melodies often draw on anhemitonic pentatonic modes and flexible, speech‑like rhythms, while textures tend toward solo voice with drone, or sparse heterophony from a small ensemble.

Songs commonly praise mountains, taiga, and rivers, recount heroic epics and clan histories, and invoke Tengrist cosmology, blending practical herder life with a spiritual view of nature.

Altai music grew from the lifeways of nomadic and semi‑nomadic Turkic‑Mongolic peoples in the Altai Mountains. For centuries, epic bards and kai‑singers transmitted history, ethics, and cosmology entirely by ear, using flexible rhythms and modal melodies suited to storytelling and the open landscape. The imitation of natural soundscapes—wind, hoofbeats, birdcalls—became an aesthetic hallmark, supported by overtone techniques (kai) and simple drone accompaniments on the topshur and khomus.

Russian explorers, missionaries, and ethnographers documented Altai musical practices in the 1800s and early 1900s. Wax cylinders, later discs and notations, captured epic genres and ritual songs, while local instrument building (topshur/topshuur variants, shoor flutes) was described in detail. Cross‑regional exchange with Tuvan and Mongolian performers further shaped the vocal styles and repertoires across the Altai–Sayan cultural zone.

During the Soviet era, regional song‑and‑dance ensembles arranged village repertoire for stage performance. This professionalized the tradition, standardizing tunings and forms, adding choral textures, and placing the topshur, shoor, and khomus into orchestrated contexts. While ritual contexts narrowed, broadcast and touring expanded the music’s reach inside and outside the USSR.

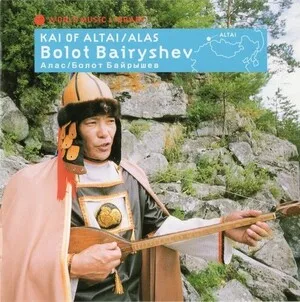

After the 1990s, local ensembles and culture bearers revived epic performance and kai techniques, often engaging in cultural festivals and recordings. Contemporary groups balance authenticity with new media and occasional fusion—pairing topshur and shoor with guitar, bass, or ambient textures—bringing Altai music to world stages while maintaining narrative content rooted in landscape and Tengrist worldview.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)