North Asian music is an umbrella term for the traditional and contemporary musical practices of the peoples of Mongolia and Siberia (including Tuvan, Buryat, Sakha/Yakut, Altai, and other Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic groups).

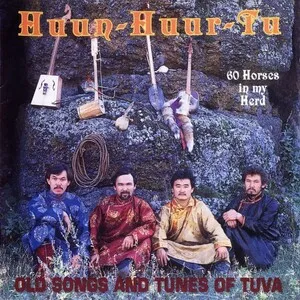

It is characterized by overtone-rich vocal techniques (such as khöömei/khöömii throat singing), expansive long-song styles, pentatonic and modal melodies, open-fifth drones, jaw harp timbres, and ritual drumming. Signature instruments include the morin khuur (horsehead fiddle), igil (two‑string spike fiddle), topshuur and doshpuluur (lutes), limbe (flute), and the khomus (jaw harp).

Socially, the music spans epic recitation, shamanic-ritual sound, herding songs tied to pastoral lifeways, and modern stage ensembles that adapt these idioms for concert and global audiences.

North Asian music grows from nomadic and semi‑nomadic lifeways on the steppe and taiga. Vocal timbres and instruments imitate wind, river, and animal sounds, reflecting animist and shamanic cosmologies. Long before written documentation, epic singing, ritual drumming, and jaw‑harp playing were used for storytelling, healing, and community rites.

During the Mongol Empire, court and camp music traveled widely. Envoys and travelers described praise songs, long‑song performance, and flute and fiddle traditions. Although earlier practices existed, this period increased cross‑regional circulation between North and Central Asia and established emblematic forms like long song (urtyn duu) and early overtone-singing practices.

By the early modern era, the morin khuur and related spike fiddles, jaw harps (khomus), and frame drums were firmly embedded in local cultures. Vocal techniques diversified into distinct throat‑singing styles (e.g., sygyt, kargyraa, khöömei), and narrative epics and praise genres (tuuli, magtaal) flourished. Melodies tended to be pentatonic with wide contours, glides, and open-fifth drones.

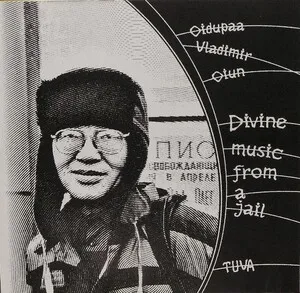

Soviet-era cultural policy and state ensembles codified regional repertoires for stage performance, preserving many forms through notated arrangements and radio archives while reshaping others. Ethnographic fieldwork (mid‑1900s onward) documented village practices, and recording technology brought Tuvan and Mongolian singing to global listeners.

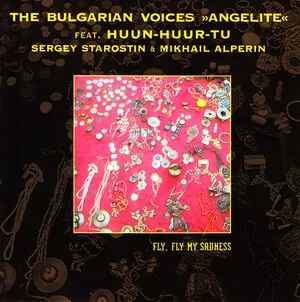

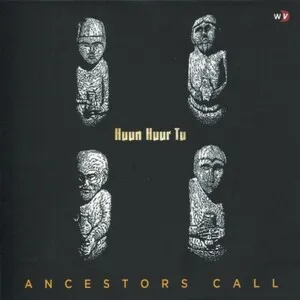

From the 1990s, ensembles and soloists toured internationally, inspiring collaborations with jazz, rock, ambient, and new‑age scenes. Throat singing and horsehead fiddle timbres became emblematic sounds in world‑fusion, film scores, and experimental music, while community practitioners continue to sustain local ritual and pastoral contexts.