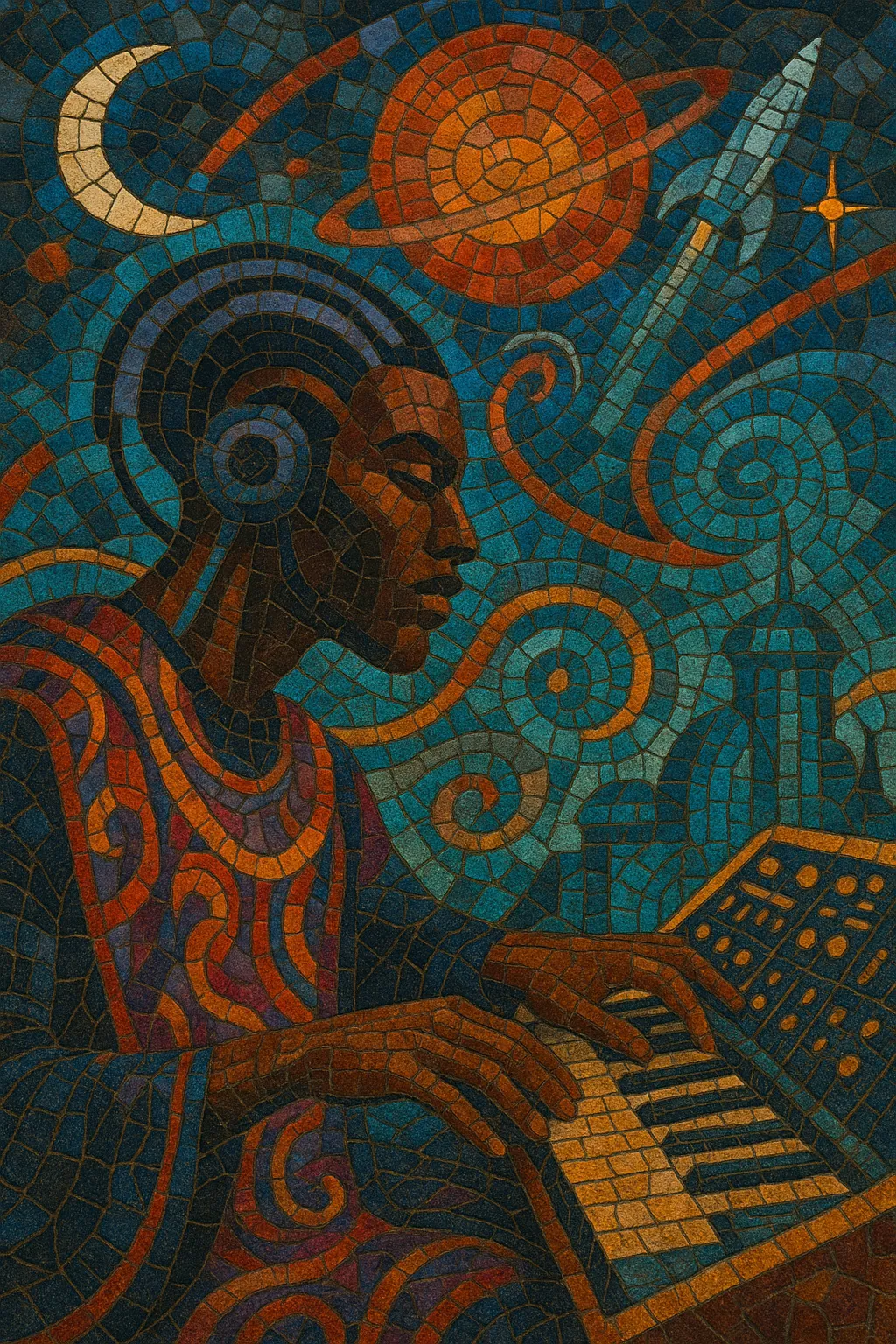

Afrofuturism in music blends Black diasporic musical traditions with science-fiction, speculative history, and visions of liberated futures. It fuses the grooves of funk and soul, the harmonic adventurousness of jazz, and the synthetic timbres of electronic music with cosmic imagery, myth-making, and techno-utopian (and often techno-critical) narratives.

Sonically, it favors analog and digital synthesizers, vocoders and talkboxes, spacey effects, hypnotic basslines, and polyrhythmic drumming that points back to African rhythmic logics. Lyrically and visually, it imagines alternate timelines, extraterrestrial migrations, underwater civilizations, and high-tech Black modernities as vehicles for cultural memory, self-determination, and critique.

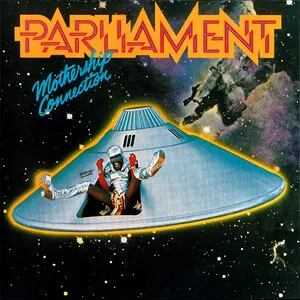

Afrofuturism’s musical roots coalesce in the mid-20th century, before the term existed. Jazz bandleader Sun Ra forged a cosmic big-band language, blending big-band swing and avant-garde jazz with mythology, Egyptian iconography, and interstellar narratives. In the 1970s, George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic turned these ideas into mass-culture spectacle, building a P-Funk cosmology of motherships, clones, and funk as emancipatory technology. Parallel currents ran through soul, psychedelic soul, and experimental electronic music that embraced space-age timbres and speculative themes.

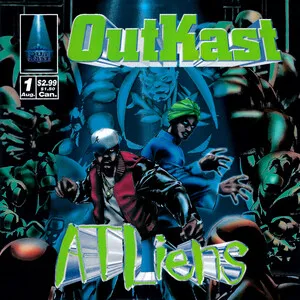

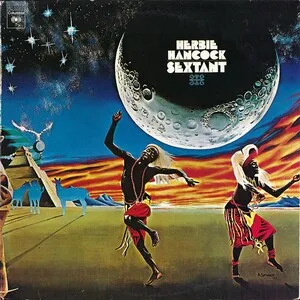

Electro and early hip hop picked up the sci-fi baton: Afrika Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock” and Herbie Hancock’s “Rockit” mainstreamed robotic grooves, vocoders, and futuristic video aesthetics. In Detroit, the techno innovators (especially Juan Atkins/Model 500 and later Drexciya) encoded science-fiction narratives and Black modernist thought into machine music. The term “Afrofuturism” was coined in 1993 by cultural critic Mark Dery; writers like Kodwo Eshun expanded its theoretical frame, retroactively linking Sun Ra, P-Funk, and techno under a shared aesthetic-philosophical project.

From the 2000s onward, Afrofuturism flourished across neo-soul, alternative hip hop, leftfield electronic, and the global jazz renaissance. Janelle Monáe’s android suites, Flying Lotus’s astral beat collages, Shabazz Palaces’ opaque sci-fi rap, and Drexciya’s enduring mythology exemplify its breadth. In jazz, The Comet Is Coming and Shabaka Hutchings channeled cosmic energies into contemporary improvisation. Visual culture (fashion, film, performance art) intertwined with music, notably in the Black Panther era, cementing Afrofuturism as a living, evolving continuum rather than a single sound.

Across eras, Afrofuturism uses speculative storytelling to address history and futurity: space travel and exile, technological empowerment and surveillance, submerged (“underwater”) histories, and the reimagining of Black presence in times and spaces denied by dominant narratives. Its sonic signatures—synth-forward palettes, deep funk grooves, polyrhythms, and expansive harmony—serve as vehicles for both celebration and critique.