West Asian folk music is the umbrella for vernacular song and dance traditions from Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, the Iranian plateau, and the Arabian Peninsula.

It is tied together by shared modal systems (maqām, dastgāh, and mugham), asymmetrical and cyclical rhythms (iqāʿ/usûl such as 10/8 samāʿī, 9/8 karsılama, 7/8 and 5/8 aksak patterns), heterophonic textures, and rich microtonal ornamentation. Signature timbres come from instruments like the oud, bağlama/saz, tar, kamancheh, qanun, santur, ney, duduk, zurna, davul, darbuka (doumbek), riqq, daf, bendir, and frame drums.

Repertoires span epic narrative songs (dāstān/ashugh traditions), love lyrics, lullabies, laments, seasonal/work songs, circle dances (e.g., dabke, halay), and devotional/Sufi repertoires. Transmission has historically been oral, rooted in social life—weddings, coffeehouses, communal rites—and later amplified by radio, records, and diaspora scenes.

Folk practices in West Asia draw on ancient Near Eastern musical lifeways, later articulated in medieval theory. Between the 10th–13th centuries, Arabic and Persian scholars codified modal thinking (maqām/dastgāh), while oral village and bardic traditions maintained local scales, tunings, and dance rhythms.

Under Seljuk, Ottoman, and Safavid spheres, itinerant bards (ashugh/aşık), urban artisans, and Sufi orders cross‑fertilized repertoires. Courtly theory influenced popular practice, yet folk idioms retained heterophony, microtonal nuance, and regionally distinct meters. Instruments like oud, saz, kamancheh, and frame drums spread widely, while local variants (duduk, zurna–davul pairs) anchored communal rites.

Print culture, gramophones, and radio documented and standardized village songs and dance forms. National folklore projects (e.g., in Turkey and Iran) collected tunes, organized state ensembles, and adapted rural materials for urban stages. In the Levant and Caucasus, theatre and café music blended folk melodies with modern harmony and large ensembles.

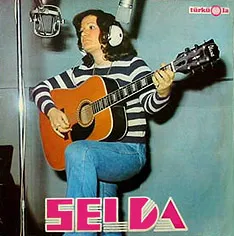

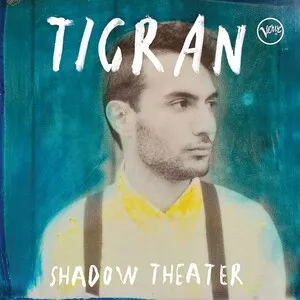

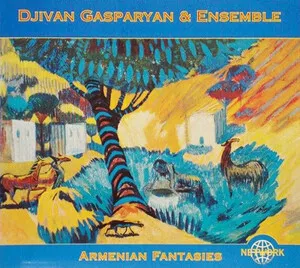

Broadcast media and migration spread West Asian folk globally. Folk sounds fed into popular styles (e.g., Rahbani/Fairuz’s Lebanese songcraft, Anatolian türkü revivals, Kurdish and Armenian folk renaissances). Post‑2000s, archival projects and UNESCO recognitions boosted preservation, while contemporary artists mix traditional modes and rhythms with pop, rock, and electronic textures—without losing core modal, rhythmic, and timbral identities.

Start by selecting a mode from a regional system: an Arabic maqām (e.g., Rast, Bayātī, Ḥijāz), a Persian dastgāh/āvāz (e.g., Shur, Segāh), or an Azerbaijani mugham (e.g., Shur, Rast). Internalize its scale degrees, tetrachords, microtonal inflections, and characteristic melodic pathways (sayr/guše). Intonation matters more than equal‑tempered accuracy—listen and sing along to master shades between semitones.

Pick an iqāʿ/usûl that matches your song or dance: 4/4 maqsum or saidi for accessible grooves; 10/8 samāʿī for lyrical pieces; 9/8 karsılama or 7/8 aksak for driving dances; 2/4 dabke for communal energy. Use ostinato patterns on frame drums (daf/bendir), riqq, darbuka, or davul to articulate accents. Structure pieces with a free‑time instrumental improvisation (taqsīm/peşrev‑like prelude) leading into strophic verses and refrains, and consider a mid‑song modulation to a closely related mode.

Compose singable, stepwise melodies with expressive leaps and frequent ornamentation: slides, grace notes, trills, mordents, and melismas. Arrange heterophonically—a unison melody line subtly varied by voice and instruments rather than harmonized in chords. Leave space for call‑and‑response between lead voice/instrument and ensemble.

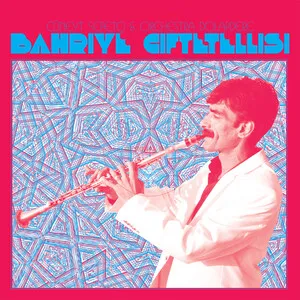

Core options include oud or bağlama/saz for melody and drone; tar or kamancheh for lyrical lines; qanun or santur for shimmering arpeggios; ney for breathy, contemplative color; zurna with davul for outdoor dance pieces; duduk for lamenting tones. Percussion (daf, bendir, riqq, darbuka) supplies the groove; alternate hand techniques (tek/dum/ka) to articulate the cycle.

Write verses in a relevant language (Arabic, Turkish, Persian, Kurdish, Armenian, Azeri, etc.). Themes often center on love and longing, spiritual yearning, nature, homeland, and epic memory. Short quatrains or narrative couplets work well; match prosody to the rhythmic cycle.

Favor intimate, live‑room recording; capture frame drums with room mics plus a close mic on the riqq/darbuka for definition. Pan melodic instruments to preserve heterophony and avoid dense chordal pads. Let microtonal bends lead the phrasing, and place the groove slightly behind the beat for earthy propulsion.