Vocalese is a jazz vocal style in which singers write and perform original lyrics to pre‑existing instrumental melodies, improvised solos, and full ensemble arrangements.

Unlike scat singing—which uses non‑lexical syllables—vocalese uses fully formed words that mirror the exact rhythms, inflections, and contours of the original instrumental lines. The result is virtuosic, text‑driven performances that retain the swing feel, bebop phrasing, and harmonic sophistication of modern jazz.

Vocalese is frequently realized by soloists and by vocal groups that harmonize transcriptions of big‑band or small‑group arrangements, often employing tight, jazz‑choral voicings and brisk, swinging tempos.

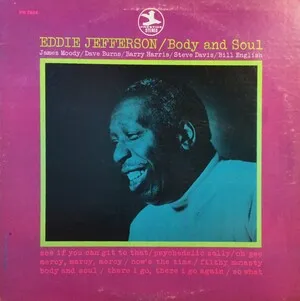

Vocalese emerged in the United States in the early–mid 1950s as jazz singers began crafting lyrics to well‑known instrumental solos and ensemble lines. Pioneers like Eddie Jefferson helped define the concept by setting words to bebop saxophone improvisations, preserving every rhythmic nuance and pitch.

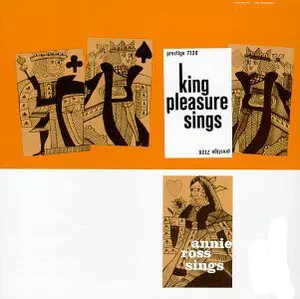

King Pleasure popularized the approach with widely heard recordings that brought the idiom to a broader audience, showing that intricate bebop language could be sung—word for note—with narrative lyrics.

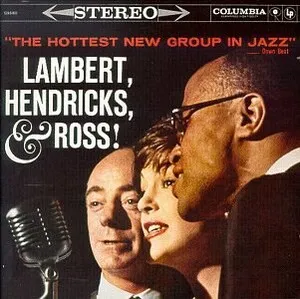

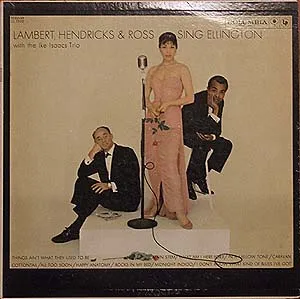

The style reached a creative peak with Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. Their landmark recordings set entire big‑band arrangements—especially from the Count Basie book—to lyrics, often using overdubbing and meticulous multi‑part arranging. Their work demonstrated that vocalese could function as both virtuosic solo craft and as a fully orchestrated vocal‑jazz architecture.

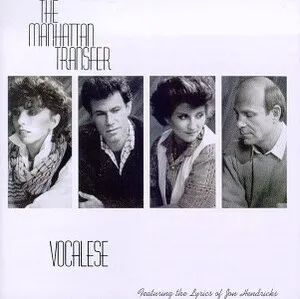

From the 1970s onward, The Manhattan Transfer revived and expanded the idiom for new audiences, culminating in ambitious projects that paid homage to classic jazz soloists and writers. Subsequent artists and ensembles—Kurt Elling, New York Voices, and others—have continued the tradition, applying vocalese to post‑bop, modal, and contemporary jazz sources and keeping the craft alive on stages, in studios, and in jazz education.

Select a recorded jazz solo or ensemble passage with a clear, singable contour—often from bebop, swing, or big‑band recordings. Ensure you can accurately transcribe every pitch, rhythm, articulation, and inflection.

Write lyrics that map syllable‑for‑syllable to the solo’s phrasing. Match consonants to articulations (e.g., tongued eighths, accents) and place vowels to sustain longer notes. Maintain natural word stress while preserving the solo’s rhythmic syncopation. Narrative or character‑driven texts work well, but clarity and breath planning are essential.

For group vocalese, distribute horn‑section or ensemble lines into SATB (or similar) parts using close jazz voicings, guide‑tone lines, and extensions (9ths, 11ths, 13ths). Respect the original harmony (ii–V–I cycles, tritone subs, altered dominants) and notate passing chords implied by the line. Consider call‑and‑response between lead (solo transcription) and background (pad figures, riffs).

Keep swing eighths consistent and lock into the pocket with the rhythm section. Fast bebop lines demand crisp diction and unified time feel. Use anticipations, back‑phrasing, and subtle scoops judiciously to mirror the instrumental style without obscuring lyric intelligibility.

Chunk difficult passages, drill vowels on sustained notes, and practice with metronome on off‑beats to internalize swing. Confirm breath marks that align with the original solo’s phrasing.