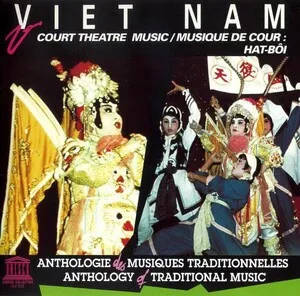

Vietnamese opera is an umbrella term for Vietnam’s sung-theatre traditions—tuồng (hát bội), chèo, and the later cải lương—that fuse music, poetry, stylized gesture, dance, and symbolic stagecraft to tell historical, martial, romantic, and comic stories.

Musically, these forms draw on pentatonic modal systems (variously called hơi), heterophonic textures, flexible tempi, and highly ornamented vocal lines. Percussion—especially the trống chầu (cue drum)—punctuates action and guides performers, while lutes, fiddles, zithers, flutes, and small gongs/cymbals color the ensemble. Tuồng emphasizes codified role types and face painting; chèo favors satirical, village-based narratives; and cải lương blends southern nhạc tài tử chamber aesthetics with Western dramaturgy and the signature vọng cổ aria.