Your digging level

Description

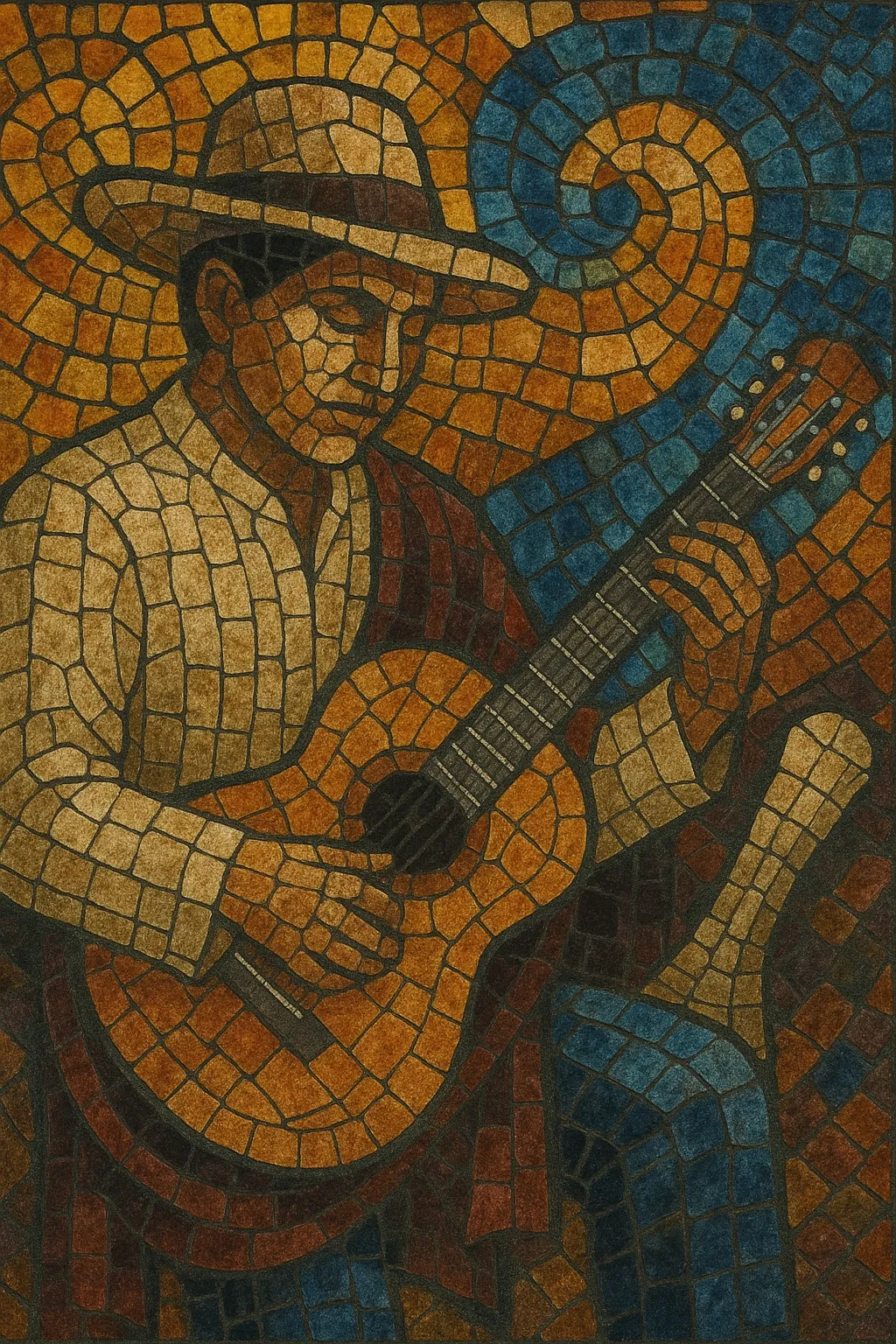

Vals venezolano is the Venezuelan creolized form of the European waltz, rendered in 3/4 time but colored by local rhythmic flex, rubato, and folkloric accompaniment.

It is performed both instrumentally (most famously on solo guitar, piano, harp, and mandolin) and as a vocal salon song with romantic and nostalgic lyrics. The accompaniment often goes beyond a strict oom‑pah‑pah, introducing syncopations, occasional hemiola feels (3:2 cross‑rhythms), and idiomatic ornamentation that reflect Venezuelan popular and folk practices.

Harmonically it draws from 19th‑century Romantic language—lyrical melodies, chromatic passing tones, secondary dominants, and graceful modulations—yet it remains intimate and dance‑derived, bridging salon elegance and criollo expressivity.

History

European waltzes arrived in Venezuela during the mid‑19th century via salon culture in cities such as Caracas and Valencia. As the waltz became fashionable among the creole elite, local musicians and composers adapted it to domestic instruments (piano, guitar, mandolin) and to Venezuelan tastes—lighter textures, melodic ornamentation, and a flexible pulse.

By the late 19th century, the Venezuelan waltz had distinct idioms. Composers like Heraclio Fernández popularized spirited pieces such as “El Diablo Suelto,” while salon pianists and guitarists cultivated lyrical valses that circulated as sheet music and in parlor performances. The genre absorbed rhythmic nuances from regional practices (including cross‑rhythms known from joropo performance), yielding accompaniments that could momentarily imply 6/8 against 3/4.

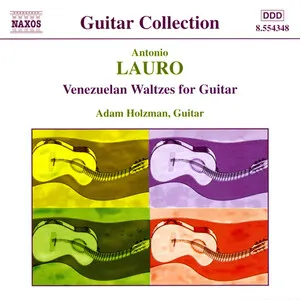

In the 20th century, the vals venezolano became a cornerstone of the Venezuelan guitar repertoire. Antonio Lauro’s celebrated Valses Venezolanos (e.g., “Natalia,” “Andreína,” “El Marabino”) codified a national guitar style, recorded and championed by virtuosos such as Alirio Díaz. Orchestral arrangers like Aldemaro Romero and bandleaders helped the genre migrate from parlor to concert stage and radio, while singers brought the form into the urban popular songbook.

Today, vals venezolano remains a living tradition: taught in conservatories, performed by folk ensembles (harp, cuatro, maracas), classical guitarists, and pianists, and sung in nostalgic salon style. Its pieces are standards for Venezuelan musicians at home and abroad, and they continue to influence Latin American classical programming and guitar pedagogy.