Tibetan music encompasses the ritual sounds of Tibetan Buddhism, secular folk repertoires from the plateau, and theatrical forms such as lhamo (Tibetan opera). It is marked by powerful long-horn fanfares (dungchen), piercing double-reed calls (gyaling), metallic cymbal textures (rolmo), frame and hand drums (damaru, nga), and deep multiphonic monastery chant.

Melodically, many secular songs are pentatonic with graceful ornaments and narrow ambitus suited to high-altitude vocal production, while liturgical chant emphasizes sustained drones, modal centricity, and mantra recitation rather than functional harmony. Core genres include devotional chant, the urban salon styles nangma and toeshey of Lhasa, pastoral folk songs, and ceremonial dance music (cham) accompanying masked rituals.

Texts are often in Tibetan and center on devotion, moral teachings, nature, and epic-historical themes. The sound world ranges from thunderous, epic temple ensembles to intimate, contemplative singing with dranyen (Tibetan lute) and piwang (spike fiddle).

Tibetan music took shape during the Tibetan Empire, when indigenous shamanic and court traditions met Buddhist ritual practice arriving from India via the Silk Roads. Early ceremonial horns, conches, and chant framed royal and religious rites, establishing a template for large outdoor and temple ensembles.

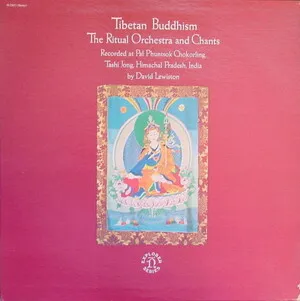

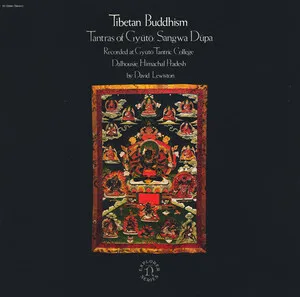

As Buddhist schools spread, monasteries codified liturgical repertoires: deep multiphonic chanting (gyuke), responsorial textures, and set cycles for puja and cham (masked dance). Instruments such as dungchen (long horns), gyaling (double reeds), rolmo (cymbals), and a spectrum of drums were standardized. Mantra recitation and modal chant styles became central, privileging timbre, drone, and rhythm over harmonic progression.

Urban salon genres—nangma and toeshey—flourished in Lhasa, drawing on Central and East Asian court aesthetics but localized in pentatonic melodies and Tibetan poetry. Lhamo (Tibetan opera) developed as a narrative singing-dance-theatre form with stock roles, chorus, and instrumental interludes, often performed at festivals.

Political upheavals, exile, and modern media reshaped Tibetan music. Monastic chant reached global audiences through field recordings and tours. In exile communities (India, Nepal, later the West), artists blended traditional instruments with acoustic and electronic arrangements, while folk-pop carried Tibetan language and identity to new listeners.

From the late 20th century onward, Tibetan vocal and instrumental timbres—dungchen blasts, singing bowls, overtone chant—entered ambient, new age, and meditation scenes worldwide. Contemporary Tibetan singers and ensembles preserve liturgical and folk repertoires, innovate within nangma/toeshey, and collaborate across world, classical, and electronic contexts.