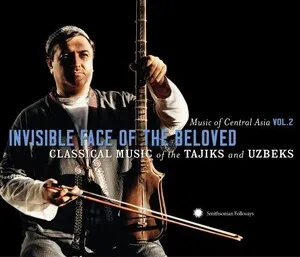

Tajik music encompasses the traditional, classical, and popular music of the Tajik people in Tajikistan and the broader Central Asian region (notably Bukhara, Samarkand, and the Pamirs). It is rooted in Persianate culture and the maqam modal system, with Tajik language (a variety of Persian) and Pamiri languages shaping its poetic and vocal aesthetics.

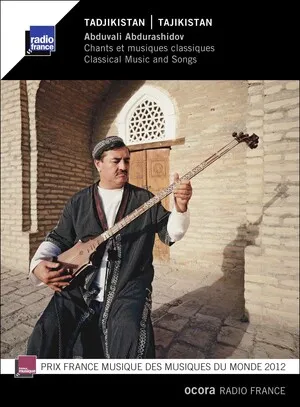

Its classical pillar is the urban suite tradition of Shashmaqam, while the emblematic mountain style Falak expresses laments and ecstatic praise through highly ornamented, often rubato singing. Pamiri music from Badakhshan adds distinctive modal colors, meters, and polyphonic textures. Across styles, typical instruments include the dutar and tanbur (long‑necked lutes), ghijak/kamancheh (spike fiddle), rubab, nay/ney, and the doira frame drum. Modern Tajik pop blends these timbres and rhythms with contemporary production, keeping the melodic contours and poetic sensibilities of the tradition.

Tajik music reflects centuries of Persianate court culture, Sufi spirituality, and mountain folk traditions. Its core urban classical repertoire coalesced into the Shashmaqam suite tradition, while village and highland practices continued to evolve as living folk genres (notably Falak and diverse Pamiri styles).

Following the Islamization of Transoxiana (Mawarannahr), Tajik‑speaking urban centers like Bukhara and Samarkand absorbed and localized the broader maqam system known across the Persian and Arab worlds. Courtly music developed around Persian poetry (Rudaki, Hafez, Rumi), improvised vocalism, and skilled instrumentalists on lutes, fiddles, and flutes.

By the 18th century, urban musicians in Bukhara codified Shashmaqam (“six maqams”) into extended vocal‑instrumental cycles built on six principal modal families (Buzruk, Rost, Navo, Dugoh, Segoh, Iroq). This Tajik‑Uzbek classical repertoire standardized forms, modal progressions, and rhythmic cycles, becoming the keystone of Tajik classical identity.

Parallel to court music, rural Tajik communities sustained wedding songs, dance tunes in compound meters, and narrative song genres. In southern Tajikistan, Falak (literally “fate”/“firmament”) crystallized as an expressive, often declamatory vocal tradition that moves between free rhythm and propulsive doira grooves. In Badakhshan, Pamiri music (in Shugni and related languages) developed characteristic melodic turns, heterophony, and occasional multi‑part textures.

State theaters, conservatories, and radio ensembles archived, arranged, and staged traditional repertoires. Orchestration introduced accordion, clarinet, and Western strings, while Tajik composers such as Ziyodullo Shahidi integrated maqam modalities into symphonic and chamber works. Canonical Shashmaqam and Falak repertoires were documented and toured, shaping a national style.

After 1991, cultural policy and grassroots initiatives fueled renewed interest in Shashmaqam, Falak, and Pamiri repertoires, alongside a thriving pop scene. Artists revitalized doira‑driven dance music, re‑set classical poetry, and fused dutar/tanbur timbres with electronic production. Cross‑border exchanges with Persian, Afghan, and Uzbek musicians remain active, while UNESCO recognition of Shashmaqam underscored its Tajik heritage.