A symphony is a large-scale composition for orchestra, typically cast in multiple movements that contrast in tempo, key, and character. In the Classical era, the most common layout was four movements: a fast opening movement (often in sonata form), a slow movement, a dance-like movement (minuet or later scherzo), and a fast finale.

Over time, the symphony evolved from compact works of the mid-18th century into expansive, architecturally ambitious statements in the 19th and 20th centuries. Composers increasingly treated the symphony as a vehicle for thematic development, cyclical unity, and dramatic narrative—sometimes programmatic, sometimes abstract—using the full coloristic range of the modern orchestra.

While rooted in Classical balance and clarity, symphonies incorporate a wide spectrum of harmonic languages and orchestral techniques. From Haydn’s wit and structural innovation to Beethoven’s heroic scope, Mahler’s cosmic breadth, and Shostakovich’s modern intensity, the symphony has remained a central pillar of Western concert music.

The symphony emerged in the 1750s from the Italian opera sinfonia (overture) and the Baroque orchestral suite. Early contributions by composers such as Giovanni Battista Sammartini and the Mannheim school shaped the orchestral idiom: clear thematic contrasts, dynamic effects, and standardized instrumental sections.

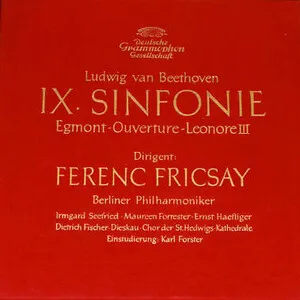

Joseph Haydn codified the four-movement scheme and developed sonata form into a powerful engine for thematic contrast and transformation. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart refined lyricism, orchestration, and dramatic pacing. Ludwig van Beethoven expanded scale, rhetoric, and harmonic ambition, redefining the symphony as a public, expressive statement of profound scope.

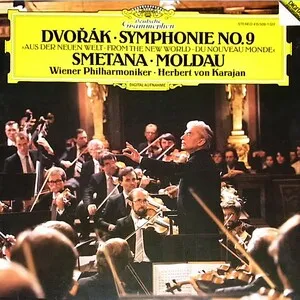

Franz Schubert enriched melodic breadth and harmonic color. Hector Berlioz introduced programmatic approaches and novel orchestration. Johannes Brahms balanced Classical rigor with Romantic warmth, while Anton Bruckner enlarged the architectural and spiritual dimensions of the form. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky emphasized emotive melody and dramatic climaxes, bringing the symphony to broader audiences.

Gustav Mahler stretched duration, orchestral size, and expressive range, integrating song, folk idioms, and philosophy. Jean Sibelius favored organic growth and motivic concentration. Modernists and nationalists adapted the form to new languages, from Sergei Prokofiev’s neoclassical clarity to Dmitri Shostakovich’s stark, often coded political narratives.

Composers continued to write symphonies in diverse idioms—tonal, modal, and atonal—often reimagining movement structures and orchestral color. The symphonic ideal influenced film scoring and symphonic hybrids in rock and metal, while contemporary orchestras and composers sustain the form with new works that dialogue with its rich tradition.

Start with a multi-movement plan, commonly four movements: fast–slow–dance–fast. Use sonata form in the first movement to present contrasting themes, modulate to a related key, develop motives, and return to the tonic for recapitulation. Consider cyclic techniques (recurring themes) to unify the whole work.

Write for a full symphony orchestra: strings (violins, violas, cellos, basses), woodwinds (flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons), brass (horns, trumpets, trombones, tuba), percussion (timpani and color instruments as needed). Expand instrumentation judiciously for color (harp, celesta, extra percussion) and balance sections so textures remain clear.

Craft memorable, contrasting themes that can withstand transformation. Use functional harmony for stability and tension, enriched by chromaticism or modal color. In development sections, fragment motives, sequence them, and explore remote keys before re-establishing the tonic.

Vary rhythmic profiles between movements (e.g., scherzo’s propulsion vs. slow movement’s long lines). Alternate textures—homophonic blocks, contrapuntal passages, chamber-like solos within the orchestra. Orchestrate themes with attention to color and register: double lines for strength, thin textures for transparency, and solo winds for lyrical relief.

• I: Energetic sonata form with clear motivic identity.

• II: Lyrical, slower, often ternary or variations.

• III: Dance-derived (minuet or scherzo) with a contrasting trio.

• IV: Brisk finale (sonata, rondo, or hybrid) that resolves the work’s tensions.

Experiment with expanded forms (continuous movements), extended techniques, polyrhythms, or new tonalities. Maintain long-range pacing: articulate climaxes, plateaus, and cadential goals so the symphonic arc remains compelling.