Your digging level

Description

Spanish classical music refers to the art-music tradition created by composers active in Spain from the Renaissance to the present, encompassing sacred polyphony, court and theatrical genres, instrumental idioms for guitar and keyboard, and nationalist currents that elevate regional dance and song types.

It is characterized by the coexistence of European common-practice techniques with distinctively Iberian colors: modal inflections (especially the Phrygian flavor), the Andalusian cadence, dance-derived rhythms (fandango, seguidilla, jota, bolero), and an idiomatic centrality of the guitar alongside choirs, keyboard, chamber, and orchestral forces.

Across centuries, Spanish composers have contributed both to pan-European classical forms (mass, motet, sonata, concerto, symphony, opera) and to uniquely Spanish hybrids (zarzuela, tonadilla), while absorbing deep historical layers that include medieval chant, Renaissance polyphony, and interactions with Sephardic, Moorish/Andalusian, and folk–flamenco traditions.

History

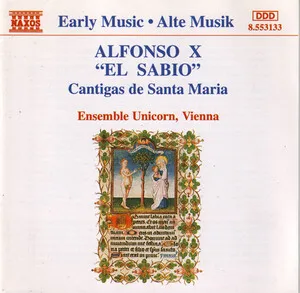

Spanish classical music crystallized in the Renaissance, building on earlier medieval foundations in the Iberian Peninsula. Sacred repertories such as Gregorian and Mozarabic chant informed the vocal language that blossomed into golden-age polyphony under Cristóbal de Morales, Francisco Guerrero, and Tomás Luis de Victoria. In parallel, the vihuela school (Luis de Milán, Luis de Narváez) created a refined instrumental tradition that prefigured the classical guitar’s central role.

The Baroque brought flourishing keyboard and guitar idioms and a vibrant theatrical culture. Gaspar Sanz codified baroque guitar practice, while court keyboard styles culminated in Domenico Scarlatti’s and Antonio Soler’s virtuosic sonatas, whose Iberian rhythms and harmonies remain emblematic. In the Classical era, figures like Luigi Boccherini, long resident in Spain, integrated Spanish dances and colors into chamber music, helping internationalize the Spanish sound within European forms.

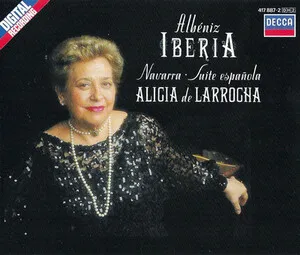

Romanticism fostered a conscious turn to national identity. Piano composers such as Isaac Albéniz and Enrique Granados elevated Spanish dance types and regional idioms into concert works, while the zarzuela tradition linked popular theater with art-music craft. Guitarist-composer Francisco Tárrega consolidated the modern classical guitar’s technique and repertoire, laying groundwork for the instrument’s global prestige.

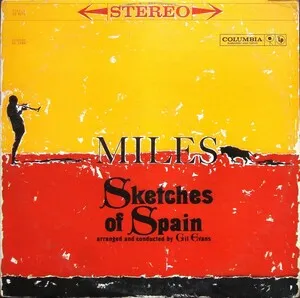

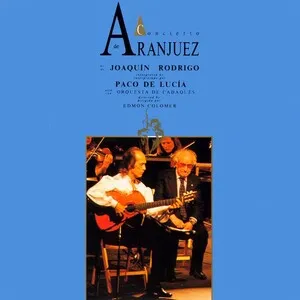

Manuel de Falla and Joaquín Turina synthesized Andalusian, folk, and flamenco elements with modern orchestral language, while Joaquín Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez became an iconic 20th‑century guitar concerto. Andrés Segovia championed the guitar worldwide, catalyzing a vast repertoire and pedagogy. Later composers, including Federico Mompou and the Halffter circle, extended Spanish classical language into impressionistic, neoclassical, and contemporary idioms, preserving the characteristic blend of European forms with Iberian timbre, modality, and rhythm.

How to make a track in this genre

Use common-practice harmony enriched with Iberian modal color, especially the Phrygian flavor and the Andalusian cadence (iv–III–II–I in minor). Incorporate modal mixture and melodic ornaments that hint at cante jondo and older chant traditions, even within tonal contexts.

Draw rhythm from Spanish dances and songs: fandango (often with hemiola between 3/4 and 6/8), seguidilla, jota, bolero, and zapateado‑like pulsations. Alternate duple/triple feels and employ syncopations that evoke guitar strumming or castanet articulations.

Feature classical guitar (idiomatic arpeggios, campanella, ligados, and rasgueado‑inspired textures), piano (granados/albéniz-style figurations), and colorful orchestral writing with bright winds and nuanced percussion. Chamber textures can spotlight guitar with strings or woodwinds; keyboard writing can emulate guitar idioms.

Favor lyrical, ornamented melodies with appoggiature and melismas in vocal lines. In instrumental writing, interleave cantabile lines with dance-derived ostinati. For sacred or historical evocations, use imitative counterpoint and transparent choral textures in the Renaissance spirit.

Shape pieces using classical forms (ternary, variation, sonata) but embed Spanish character through thematic cells derived from folk/flamenco motives. For stage or programmatic works, reference zarzuela-like contrasts between lyrical numbers and lively danza sections.

Indicate expressive rubato and dynamic nuance to capture cante‑like flexibility. Guitar parts should specify fingering and timbral indications (ponticello/tasto, apoyando/tirando). Encourage crisp articulation in dance rhythms and warm legato in lyrical passages.