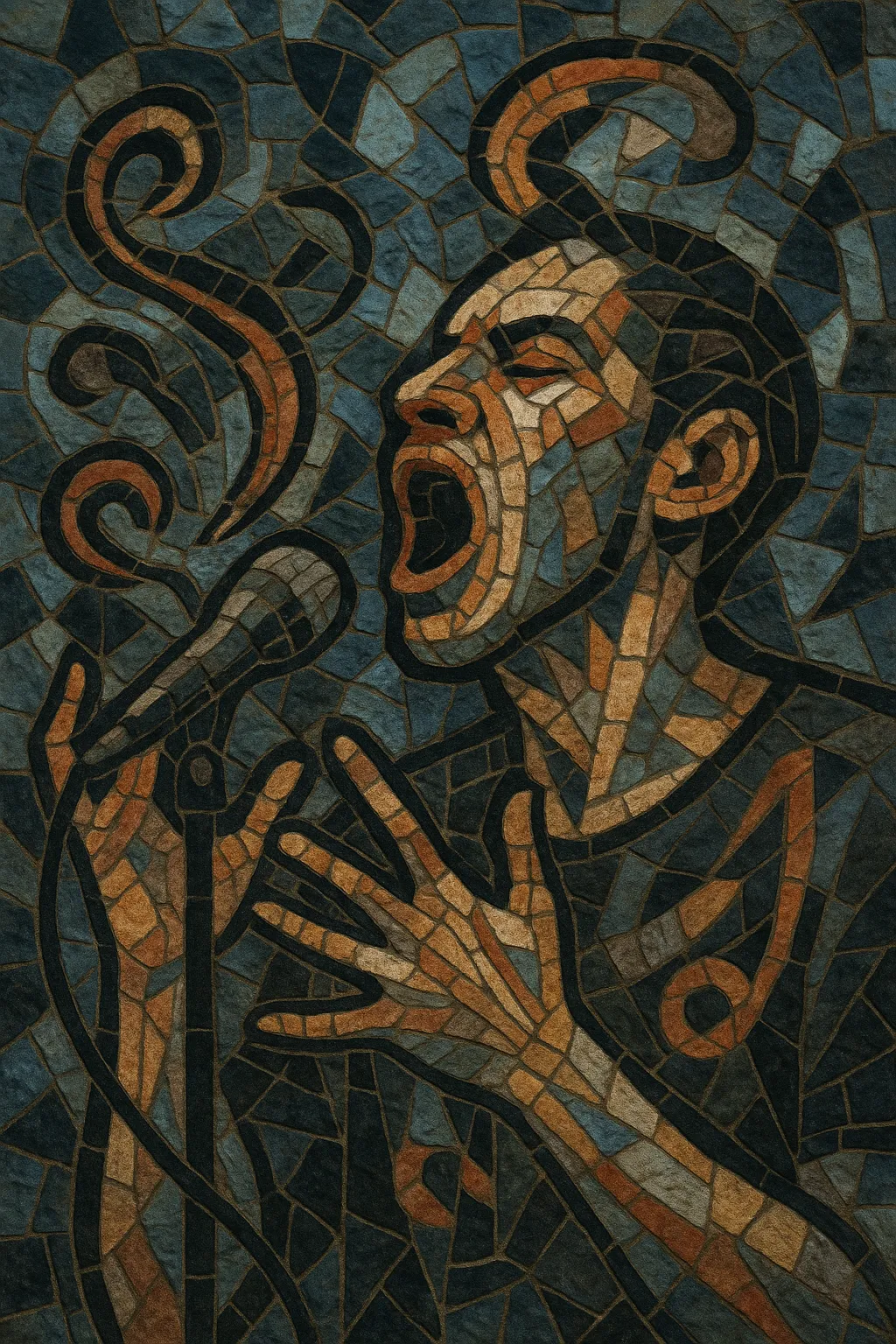

Sound poetry is a vocal and performance-centered art in which the sonic qualities of language—phonemes, rhythm, timbre, breath, and noise—take precedence over conventional meaning.

It treats the voice as an instrument, privileging articulation, texture, and extended vocal techniques (glossolalia, onomatopoeia, sputters, clicks, growls) rather than syntactic sense.

Historically linked to the Futurist and Dada avant-gardes, it later embraced microphones, tape, and studio manipulation, blurring boundaries between poetry, music, theatre, and sound art.

In performance, sound poetry ranges from minimal breath pieces to dense, rhythmically propelled vocal works, from solo utterance to ensemble structures and electroacoustic collages.

Sound poetry emerges within the historical avant-garde, notably with Italian Futurism’s parole in libertà and Swiss Dada at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire. Hugo Ball’s phonetic poems (e.g., “Karawane”) and Tristan Tzara’s performances foregrounded voice and sound over semantic meaning. Kurt Schwitters developed the long-form Ursonate (1922–1932), a seminal blueprint for extended phonetic composition. Raoul Hausmann’s optophonetic works and the Russian Zaum experiments (Khlebnikov, Kruchenykh) consolidated a transnational, anti-rhetorical poetics of the voice.

Postwar technologies catalyzed new phases. Pierre Schaeffer’s musique concrète and studio techniques influenced sound poets to adopt microphones, tape editing, and multi-tracking. Henri Chopin coined and championed “poésie sonore,” while Bernard Heidsieck’s “poésie action,” François Dufrêne’s “crirythmes,” and Bob Cobbing’s British performances expanded the field. In Scandinavia, Sten Hanson fused vocal experimentation with electronics. In Canada, The Four Horsemen (bpNichol, Steve McCaffery, Paul Dutton, Rafael Barreto-Rivera) advanced ensemble sound poetry and improvisation.

From the 1980s onward, artists such as Jaap Blonk revitalized and reinterpreted classic works (notably the Ursonate) and composed new repertoires using extended techniques. Digital audio workstations, live electronics, and looping broadened performative possibilities, linking sound poetry to sound art, electroacoustic music, and experimental theatre. Festivals, archives, and reissues have preserved historical recordings while new practitioners continue to hybridize the genre with spoken word, noise practices, and multimedia performance.

Across eras, sound poetry privileges the phonetic, rhythmic, and timbral dimensions of speech. It questions the primacy of semantic meaning and treats language as acoustic material, often staging the body, breath, and microphone as primary instruments.

Start with language as sound, not meaning. Treat phonemes, syllables, breath, and mouth noises as your "notes." Allow nonsense syllables, glossolalia, and onomatopoeia to replace or intermingle with semantic text.

Explore extended techniques: whispers, growls, clicks, tongue rolls, inhaled phonation, percussive consonants, and overtone-like resonances. Vary timbre by changing mouth shape, tongue position, and airflow. Use dynamics from near-silence to shouts, and contrast continuous streams with sharp, percussive bursts.

Organize material by pulse, repetition, and permutation. Build motifs from short phonetic cells; sequence them in additive/subtractive patterns, canons, or call-and-response. Use silence structurally. Consider strophic forms (repeating sections) or long-form arcs (as in Ursonate-style movements).

Compose with the mic as instrument: proximity effect, plosives, breath noise, and feedback become expressive tools. Employ delay, reverb, looping, and layering to create counterpoint between vocal lines. Tape or DAW editing can rearrange takes into collages, granulate phonemes, or time-stretch breaths into drones.

Invent flexible scores: phonetic strings, graphic symbols, or timed instruction cards. For ensembles, assign registers, textures, or phoneme sets to each performer and cue transitions by gesture or clock time. Rehearse balance, blend, and spatialization (surround placement or movement through the room).

Stage the body: posture, gesture, and distance to the mic shape the sound. Consider lighting and simple objects (paper, resonant tubes) to extend timbre. Keep durations focused; let contrast between sections clarify structure.