Smooth jazz is a radio-friendly offshoot of jazz that blends the harmonic vocabulary and improvisational flavor of jazz with the gentle grooves of R&B, pop, and easy listening. It emphasizes melody, polished production, and laid‑back rhythms over extended improvisation or complex swing feels.

Typically mid‑tempo and sleek, smooth jazz favors clean electric guitar, soprano or alto saxophone leads, warm electric piano (Rhodes) and synth pads, and a tight, understated rhythm section. The result is music designed for relaxed listening—romantic, urbane, and sophisticated—yet still rooted in jazz harmony and phrasing.

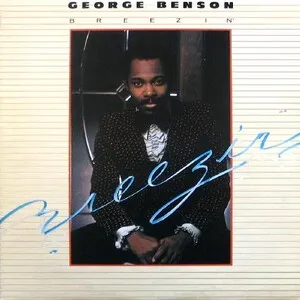

Smooth jazz coalesced in the mid‑to‑late 1970s in the United States, emerging from the accessible edge of jazz fusion and jazz‑funk. Artists and producers began favoring strong, singable melodies and mid‑tempo backbeats while keeping extended chords and jazz phrasing. Crossover hits such as George Benson’s "Breezin'" (1976) and Chuck Mangione’s "Feels So Good" (1977) demonstrated that jazz‑leaning instrumentals could succeed on pop and adult‑oriented radio.

At the same time, R&B’s Quiet Storm programming on FM radio championed lush, romantic soundscapes. This aesthetic—silky textures, polished production, and intimate mood—interfaced naturally with the mellower side of fusion and soul jazz, setting the stage for a new radio format.

In the 1980s, dedicated stations and shows codified the "Smooth Jazz" (often labeled NAC—New Adult Contemporary) format. Programming centered on saxophone‑ or guitar‑led instrumentals with occasional vocal tracks that fit the same mood. Key albums like Grover Washington Jr.’s "Winelight" (1980), Bob James’s collaborations, and David Sanborn’s sleek productions became format touchstones. By the early 1990s, artists such as Kenny G, Dave Koz, Boney James, and The Rippingtons were mainstays, and smooth jazz concerts and packaged tours drew large adult audiences.

As it grew commercially, smooth jazz drew criticism from some jazz purists who argued it prioritized texture over improvisational depth. Nonetheless, the genre’s musicianship remained rooted in jazz harmony and phrasing, and many artists moved fluidly between straight‑ahead sessions and smoother productions. The format’s success also expanded audiences for instrumental music and helped sustain a broad ecosystem of contemporary jazz festivals and venues.

In the 2000s, traditional smooth jazz radio formats contracted, but the music adapted to streaming platforms, satellite radio, and playlist culture. Artists integrated elements from neo‑soul, chillout, and downtempo, while collaborations with vocalists and producers refreshed the sound. Today, smooth jazz thrives via festivals, boutique labels, and online communities, and its mellow, melodic blueprint influences lo‑fi hip hop, lounge, and nu jazz production.