Your digging level for this genre

Description

Skiladika is a Greek urban-pop folk style associated with late-night live venues and high-energy, emotionally intense performances.

Musically, it blends laiko songcraft and modal melodies with amplified bouzouki, lush keyboards, drum machines, and pop production. Rhythmic foundations include zeibekiko in 9/8 for slow, dramatic pieces and tsifteteli or hasapiko in straight 4/4 for dance numbers. Vocals are ornamented and expressive, often using melisma and modal inflections (notably the Phrygian dominant/Hijaz sound). Lyrically, themes revolve around love, heartbreak, nightlife, and working‑class sentiment.

Culturally, the term "skiladika" originated colloquially around specific "bouzoukia" clubs, and although sometimes used pejoratively, it denotes a recognizable sound: bittersweet folk-pop with nightclub spectacle and crowd‑pleasing hooks.

History

Skiladika grew out of Greece’s laiko tradition, itself descended from rebetiko and regional folk (dimotiko), as urban nightlife expanded in the late 1970s and 1980s. Amplification, larger venues, and tourism created a demand for louder bands, faster turnaround hits, and stage spectacle. Musicians fused bouzouki‑led melodies with modern rhythm sections and synthesizers, embracing modal flavors linked to Anatolian and Arabic musical vocabularies.

During the 1980s, skiladika consolidated as a club‑centered phenomenon. Live sets were long, crowd‑interactive, and often medley‑driven, with singers taking requests and bands pivoting between zeibekiko ballads and danceable tsifteteli or hasapiko. Production adopted disco and pop elements—drum machines, chorused guitars, and string pads—while retaining bouzouki as a signature lead voice. The nightclub economy shaped repertoire, favoring direct lyrics, memorable choruses, and dramatic key changes.

In the 2000s, the skiladika sound fed into and overlapped with modern laiko and laiko‑pop. Newer stars blended radio‑ready hooks with traditional forms, while live venues continued the flower‑throwing, spotlight‑heavy aesthetics that defined the scene. Although the term can carry class or taste debates, the style’s melodic directness, danceable grooves, and emotive vocals remain central to Greek popular nightlife and have influenced neighboring Balkan pop‑folk sounds.

How to make a track in this genre

Use bouzouki (and optionally baglama) as a lead voice, supported by electric bass, drum kit or drum machine, rhythm/lead electric guitar, keyboards/synths, and occasional violin or clarinet for color. Live backing vocals enhance refrains and call‑and‑response moments.

Alternate between 9/8 zeibekiko for slow, brooding numbers (commonly grouped 2+2+2+3) and 4/4 tsifteteli or hasapiko for dance tracks. Typical tempos range from 60–80 BPM for zeibekiko ballads and 95–125 BPM for club‑friendly songs. Keep grooves steady and hypnotic to support expressive vocals.

Prioritize modal melodies with ornamental turns and melisma. Favor Phrygian dominant (Hijaz) and harmonic minor colors, with simple diatonic progressions for accessibility. Employ dramatic pre‑chorus lifts, occasional secondary dominants, and key changes (often up a semitone) to heighten choruses.

Write direct, emotive lyrics about love, separation, jealousy, nightlife, and resilience. Use vivid imagery and plainspoken phrasing suitable for audience sing‑alongs. Vocal delivery should be powerful and embellished, with sustained notes and expressive vibrato.

Structure songs verse–pre‑chorus–chorus with a mid‑song bouzouki solo. Layer string pads, subtle synth arpeggios, and chorused guitars around the bouzouki lead. Apply plate or hall reverb to vocals, compress drums and bass for punch, and leave space for audience participation in live contexts.

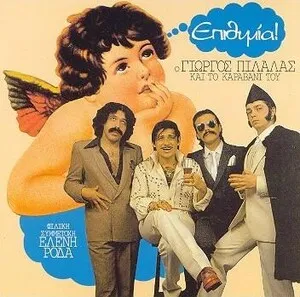

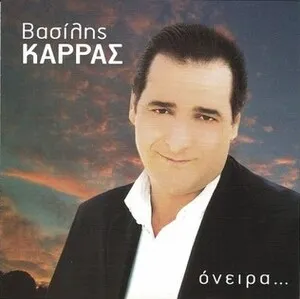

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)