Your digging level

Description

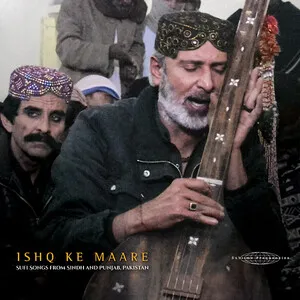

Sindhi music is the traditional and contemporary music of the Sindhi people, primarily from the Sindh region, and is most commonly sung in the Sindhi language.

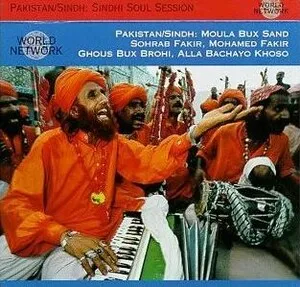

It includes a deep folk and devotional/sufi repertoire, with song-poetry traditions such as Bait (a sung poetic form) and Waee / Kafi (melodic song forms often associated with Sufi thought), alongside dance and celebratory village music.

A defining feature is the central place of poetry—especially the Sufi poetry of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai—where melodies are chosen to serve the text’s emotional meaning, spiritual reflection, and storytelling.

The sound world often blends South Asian melodic practice (raga-like modes, ornamented vocal lines) with Sindh’s local instruments and performance contexts (shrines, village gatherings, seasonal festivals, weddings).

History

Sindhi music developed as a regional tradition shaped by the Sindhi language, local folk performance, and a strong Sufi devotional culture centered on poetry.

The 18th century is crucial because Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (1689–1752) and the circulation of his poetry (notably the Shah Jo Risalo) strongly consolidated Sindhi devotional and folk singing practices, especially in Bait and Waee/Kafi-related forms.

For much of the 19th century and early 20th century, the tradition remained largely oral, maintained by hereditary musicians and community performers, and anchored in village life and Sufi shrine culture.

Radio, studio recording, and national cultural institutions increased the reach of Sindhi-language music and introduced more standardized ensembles and arrangements. Folk and Sufi repertoires were adapted for concert stages while remaining active in shrine and community settings.

Today Sindhi music continues both as a folk/devotional practice and as a modern popular identity marker. It intersects with Pakistani popular music, film and TV circulation, and diaspora communities, while many performers keep traditional instruments and poetic forms at the center.

How to make a track in this genre

Choose a groove based on the performance context:

•For Bait and more contemplative Sufi material, use a steady, restrained pulse with space for vocal rubato.

•For celebratory folk items, use more assertive cycles and handclap-friendly patterns.

•Use percussion that supports call-and-response and repetitive hooks; avoid over-complicated fills that distract from the poetry.

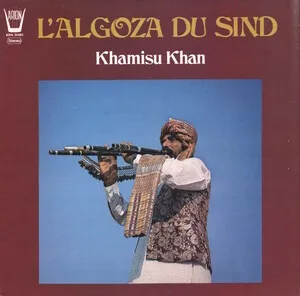

Start with a vocal lead and add one or two melodic instruments such as:

•Yaktaro / ektara-like drone-string, or regional lutes and fiddles

•Harmonium (common in devotional settings)

•Add rhythm with:

•Dholak or dhol for folk pulse

•Claps and simple frame/hand percussion for communal feel

•Arrange in layers: drone or pedal tone → melodic replies → rhythmic drive → chorus responses.

A practical structure is:

-

•

Short instrumental/drone intro setting the mode

•Verse (poetry-forward)

•Refrain or repeated line (hook) with group response

•Instrumental interlude echoing the vocal motif

•Final verses with gradual intensity and a devotional climax

Keep the hook lyrically meaningful (a repeated spiritual or moral line), not just a rhythmic slogan.

Write in Sindhi (or use translated couplets) with themes such as:

•Sufi devotion, divine love, humility, longing, moral reflection

•Folkloric stories of separation, endurance, and identity

•Use poetic devices common to the region: repetition, rhetorical questions, imagery of desert/river, journey, and beloved-as-metaphor.