Santería music (música de la Regla de Ocha/Lucumí) is the sacred Afro‑Cuban repertoire used to venerate the orishas, blending Yoruba religious song and drumming with elements absorbed in colonial Cuba.

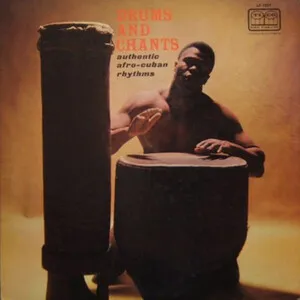

It is characterized by polyrhythmic ensembles of batá drums (iyá lead drum, itótele, and okónkolo), iron bell (ogán), and beaded gourds (chekeré). Voices are organized in call‑and‑response between a lead singer (akpwón) and a chorus, sung in Lucumí (a Yoruba-derived liturgical language) with occasional Spanish refrains. Melodies are mostly syllabic and narrow in range, prioritizing rhythm, timbre, and ritual text over harmonic development.

Performances center on codified rhythmic cycles (toques) and song suites associated with specific deities (e.g., Changó, Yemayá, Ochún, Elegguá, Ogún). In ceremonial contexts, the music serves divination, invocation, and possession trance, while public bembé gatherings and staged folkloric versions adapt the same vocabulary for secular presentation.

Santería music emerged in 19th‑century Cuba among enslaved and free Yoruba (Lucumí) communities who maintained orisha worship within cabildos (mutual‑aid/religious societies). Yoruba vocal and drum practices—especially the consecrated batá tradition—were preserved and adapted in a new social and linguistic environment. Spanish colonial and Catholic presence shaped the context (calendar, spaces, and some textual syncretism), but the core musical grammar remained West African.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, standardized repertoires of toques and song suites (e.g., the Oru del Igbodu) became widely shared across houses of worship. The consecration of batá (añá) and the role differentiation of the three drums (iyá improvising/leading, itótele dialoguing, okónkolo maintaining the timeline) were central to transmission. The akpwón’s responsorial leadership and Lucumí textual formulas linked music directly to liturgy and myth (patakí).

In the mid‑20th century, Cuban folkloric ensembles (e.g., Conjunto Folklórico Nacional de Cuba) staged orisha music for theaters and radio, bringing sacred sounds into public consciousness while maintaining ceremonial practice in religious spaces. From the 1960s–90s, recordings by iconic akpwones and batá ensembles circulated internationally, while diaspora communities in the United States and elsewhere established strong batá lineages.

From the 1940s onward, Afro‑Cuban and Latin jazz musicians integrated orisha rhythms and chants; later, salsa, rumba, and fusion groups also drew on batá textures and Lucumí coros. Contemporary projects continue to fuse Santería chant with jazz, rock, and electronic idioms, yet the consecrated ritual tradition remains distinct, guided by lineage, initiation, and strict performance protocols.