Your digging level

Description

Sakha traditional music is the indigenous music of the Sakha (Yakut) people of northeastern Siberia. It centers on epic chant (Olonkho), ritual incantations (algys), improvisatory song (toyuk), and highly developed timbral techniques, especially the khomus (Jew’s harp).

The sound world is characterized by monophonic vocal lines ornamented with glottal shakes, trills, and overtone-rich timbres; flexible, speech-like rhythms; and drones or ostinati produced by the khomus or frame drum. Much of the repertoire imitates the natural environment—wind, rivers, reindeer, horses—and encodes cosmology, ethics, and communal memory.

While deeply ancient and rooted in shamanic practice, Sakha traditional music has continued to evolve through contact with neighboring Turkic and Mongolic cultures, Russian liturgical and folk traditions, and modern stage practice.

History

Sakha traditional music likely crystallized between the 14th and 16th centuries, when Turkic-speaking Sakha communities consolidated in the middle Lena basin. It drew on earlier steppe and taiga musics, shamanic ritual (algys), and epic storytelling (Olonkho), serving as a vehicle for cosmology, social law, and environmental knowledge.

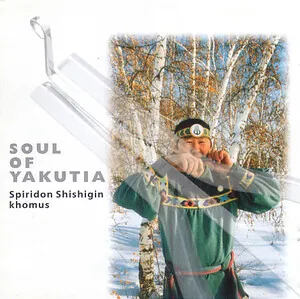

Khomus (Jew’s harp) playing developed into a virtuoso tradition, creating drones, rhythmic ostinati, and vivid onomatopoeia that mimic animals and natural forces. Vocal practice emphasized a narrow- to medium-range pentatonic language, flexible rhythm, and timbral effects over harmony.

Under the Russian Empire and later the USSR, shamanic practice was suppressed, yet folklore was collected, staged, and professionalized. State ensembles, festivals, and archives helped preserve Olonkho and khomus traditions, even as performance moved from ritual spaces to theaters. Epic narrators (olonkhosut) adapted to staged formats, and instrumental craftsmanship of the khomus was standardized and promoted.

In 2005, UNESCO proclaimed the Yakut heroic epos Olonkho a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity (later inscribed on the Representative List). The State Academic Olonkho Theatre in Yakutsk and the Khomus Museum strengthened education, research, and transmission. From the 1990s onward, performers brought Sakha timbres to global stages, inspiring collaborations with world, ambient, and folk-fusion artists.

Today, Sakha traditional music thrives across ritual practice, community festivals (e.g., Yhyakh), concert stages, and recordings. Artists fuse khomus and Olonkho chant with modern production while sustaining lineage-based pedagogy, instrument making, and repertory cycles.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)