Russian chanson is a narrative, vocal‑centered popular style rooted in early 20th‑century Russian urban song, prison ballads, and the sentimental city romance tradition. Although its name alludes to French chanson, it denotes a distinctly Russian idiom with its own vocal delivery, themes, and social context.

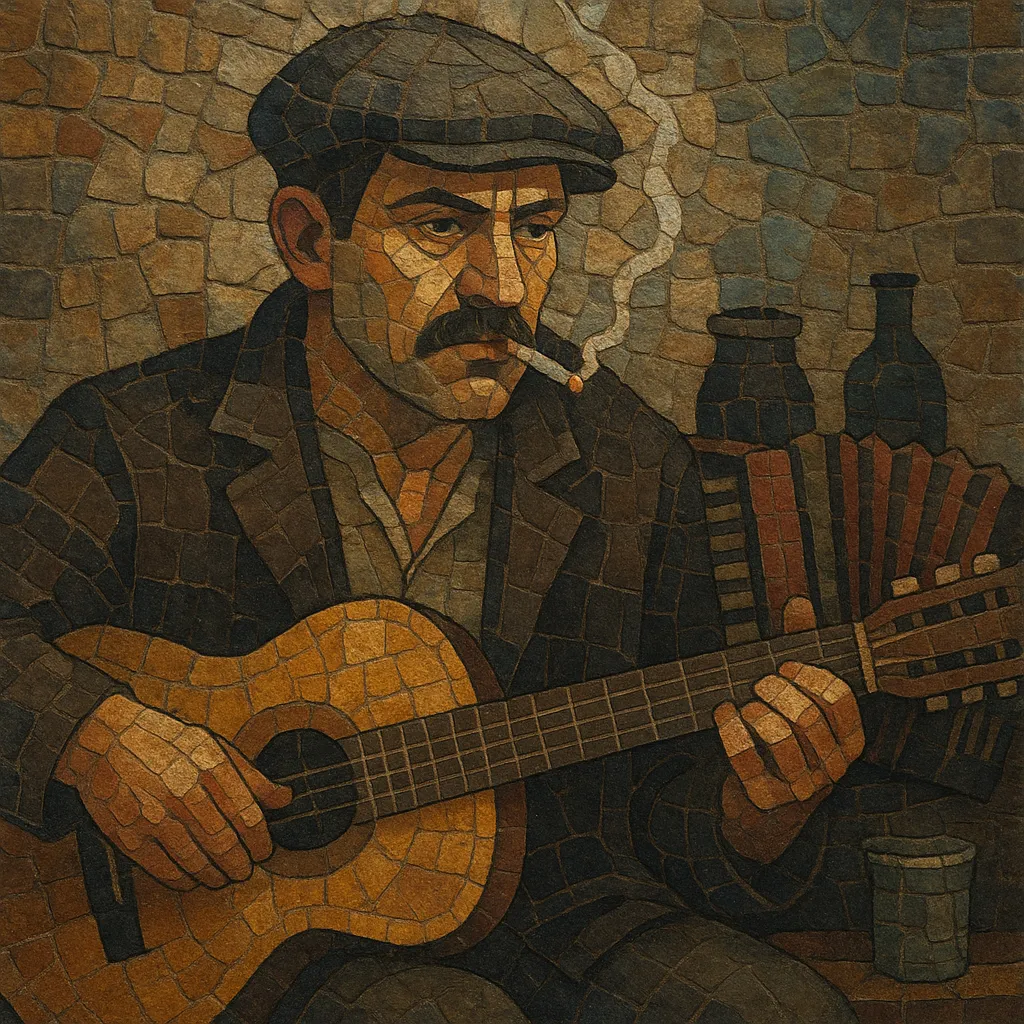

Typical topics include fate, love, longing for home, the road, friendship, war, alcohol, and the criminal underworld. Performances emphasize expressive, story‑driven singing over virtuosic instrumentation, often featuring acoustic guitar, accordion or bayan, and later, pop‑era keyboards and rhythm sections. The tone ranges from tender and nostalgic to gritty and fatalistic, and the voices are frequently warm, husky, or declamatory to foreground the lyrics.

As an umbrella for both underground “blatnaya pesnya” (thieves’ songs) and mainstream sentimental ballads, the genre crystallized as a commercial radio format in the 1990s, yet it preserves the aesthetics and storytelling methods of much older Russian song traditions.

Russian chanson grew out of two intertwined currents: the sentimental city romance (“gorodskoy romans”) and “blatnaya pesnya” (underworld and prison songs). These repertoires coalesced in taverns, workers’ districts, and performance halls of the Russian Empire and early Soviet years. Stories of love, wandering, and fatalism sat alongside narratives from the criminal milieu, framed by simple accompaniments (guitar, accordion) and a highly expressive vocal style.

During the Soviet period, official stages favored estrada (mainstream variety music), while darker, street‑level songs circulated informally. Many chanson texts lived through oral tradition and magnitizdat (home‑dubbed cassettes). The bard movement (avtorskaya pesnya) reinforced the focus on lyrics and storytelling, and performers such as Arkady Severny recorded semi‑underground albums that kept the idiom alive. Although not all bards were “chanson,” their narrative, acoustic approach strongly influenced the genre’s vocal and poetic priorities.

After the USSR’s collapse, Russian chanson moved into the open market. Dedicated radio stations, compilations, and festivals popularized the term “russkiy shanson.” Artists like Mikhail Krug, Mikhail Shufutinsky, and Lyubov Uspenskaya scored mainstream hits, solidifying the sound: narrative vocals, memorable refrains, mid‑tempo grooves, and arrangements mixing guitar, bayan/accordion, and contemporary pop rhythm sections. The repertoire broadened beyond criminal themes to include patriotic, romantic, and road songs.

The style remains a staple of Russian‑language popular music, with legacy stars, new crossover acts, and “pop‑chanson” hybrids. Streaming and YouTube have revived archival recordings and expanded regional scenes (e.g., Ural and Siberian chanson). Modern productions polish the sound with contemporary keyboards and rhythm programming, but the core—lyric‑forward storytelling, expressive vocals, and bittersweet sentiment—persists.