Romanian music is an umbrella term for the country’s rich mosaic of folk, sacred, art, and popular styles.

Its core draws on village traditions (doina laments; lively circle dances like hora, sârba, and brâul) shaped by centuries of Byzantine liturgy and Ottoman-Balkan exchange. Roma lăutari ensembles carried the urban salon sound—ornate violin, cimbalom (ţambal), accordion, clarinet, cobza, and the breathy nai (pan flute)—with melismatic singing and flexible rhythm.

In the 19th–20th centuries, composers such as George Enescu forged a national art-music voice, while post-1990 pop, rock, hip hop, and dance absorbed global currents. At home and abroad, the music is recognized for asymmetric meters (7/8, 9/8, 11/8), modal color (Dorian, Phrygian-dominant/Hijaz inflections), and a bittersweet emotional register summed up by the untranslatable feeling dor (longing).

Romanian musical identity took shape at the crossroads of East and West. Orthodox worship brought Byzantine chant into churches and monasteries, while proximity to the Ottoman world and the Balkans infused secular traditions with modal melodies, micro-ornamentation, and flexible rhythm. Village cycles of work, ritual, and festivity fostered a repertoire of doina (free-rhythm song) and social dances (hora, sârba, brâul).

Roma lăutari musicians professionalized performance at courts, inns, and salons, codifying an urban style with violin, cimbalom, cobza, and later accordion and clarinet. Their improvisatory flair and ornamentation became a hallmark of Romanian sound and spread across regions.

Nation-building spurred folklore collecting and a synthesis in art music. Composers such as George Enescu absorbed folk modes and rhythms into symphonic, chamber, and violin works, aligning Romanian music with European Romantic and modernist currents while retaining a distinct voice.

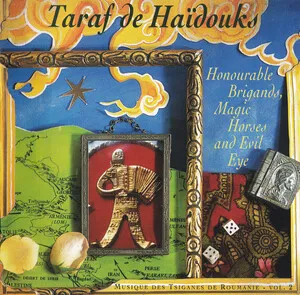

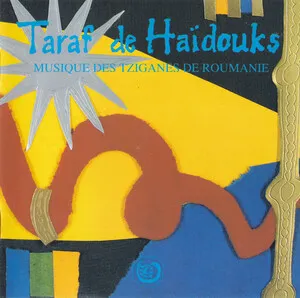

State ensembles preserved and stylized folk on stage and radio. After 1989, a flourishing independent scene emerged: rock (Phoenix), world-folk revival (Taraf de Haïdouks), brass (Fanfare Ciocărlia), hip hop and electro-folk blends (Subcarpați), and internationally oriented dance-pop (the late-2000s/2010s “Romanian Popcorn” wave) coexisted with enduring local genres like lăutărească and manele.

Romanian performers popularized the nai (pan flute) worldwide and exported distinctive meters and modal colors into global world-music, jazz, and EDM circuits, while the concept of dor continues to shape lyrical and expressive aesthetics at home.